A Tale of Two Cities: Rome and the Vatican

by Jessica Wärnberg

April 2024

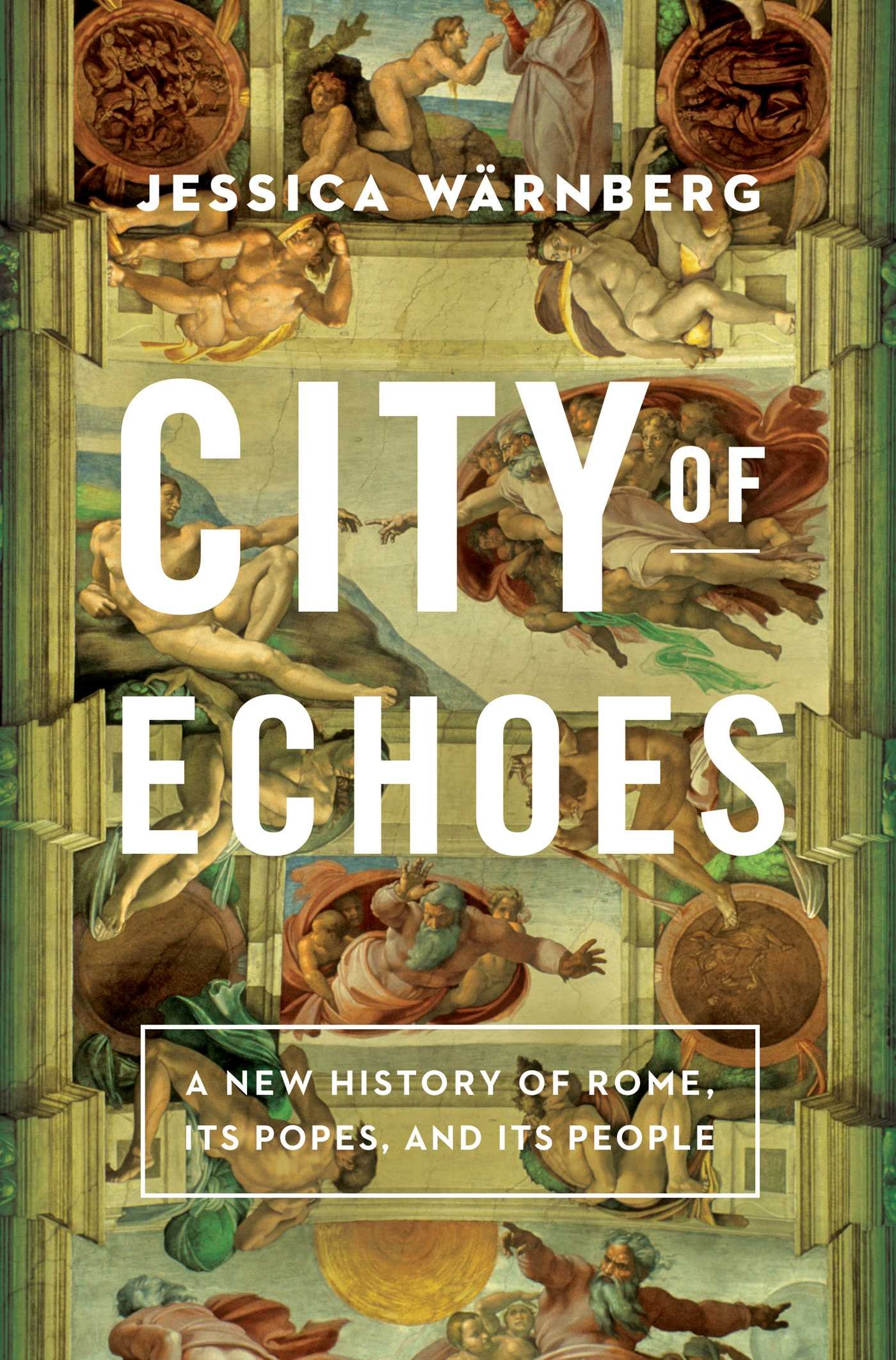

The fall of Mussolini saw Pope Pius XXII emerge as leader of the Eternal City. An extract from City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, its Popes, and its People by Jessica Wärnberg.

When bombs rained on Rome in the summer of 1943, people could scarcely believe their eyes. Men hurriedly raised brick walls around the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius. The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius was taken from the Capitoline. The world was at war and Italy with it but, until then, Rome had been spared. Since 1870, the city had been the capital of the Italian nation. Its kings and prime ministers had spent millions of lire writing a new nationalist mythology into its monuments and streets. Yet more than seventy years later, many Romans still saw themselves as the people of a papal city. In 1943, they believed that the presence of the pope in Rome would protect them from attack.

On 19 July the Romans had a brutal wake up call. In the minds of the American and British Allies, their leader was Benito Mussolini (1922–43) not Pope Pius XII (1939–58). Mussolini was a fascist who had led Italy to war shoulder-to-shoulder with Nazi Germany. In any case, the Allies would not give Rome special treatment on account of the Holy See. Even when Mussolini was arrested and King Vittorio Emanuele III (1900–46) inched towards the Allied side, appeals to protect Rome as a uniquely significant place were treated with circumspection, particularly if they came from the pope. Pius XII, himself a Roman, intervened on behalf of the city, begging President Roosevelt to ‘save our beloved Rome from devastation’. The president’s aide, the straight-talking Iowan Harry Hopkins, was sceptical, fearing ‘one hell of a row’ if Americans discovered that concessions had been made under pressure from the pope.

In the end, 9,125 bombs fell on Pius’ beloved Rome that day. The Allies aimed for the steel factory, freight yard and airport, but their bombs could not discriminate. In that single attack, 1500 civilians would die. The working-class district of San Lorenzo was devastated. It was a cruel irony that the bombs also destroyed the ancient basilica of Saint Laurence, that deacon whom imperial authorities had cooked alive for his charity to the poor. When Pius XII heard of the tragedy on 19 July he left the safety of the Vatican to bless the survivors and their dead. His bright white cassock became speckled with blood as he climbed ‘through the smoking rubble of charred houses where more than five hundred victims were strewn’. Standing over a sombre-faced crowd, the pope stretched out his arms in blessing, making his body a stark white crucifix.

Within a week of Pius’ visit to San Lorenzo, Mussolini was locked up in jail. He had been toppled by a vote of his own Fascist Grand Council and arrested swiftly afterwards by the king. Hitler was aghast as Rome’s fascists ‘melted away like snow in the sun’. It would fall to the Nazis to liberate Mussolini, installing him in a puppet state in Salò on the banks of Lake Garda in the northern region of Lombardy. It would also fall to the Nazis to restore fascist leadership to Rome. Like Pius, the Italian general Pietro Badoglio attempted to protect the capital, declaring Rome a demilitarised or ‘open’ city in August 1943. Ultimately, his efforts were vain. The Nazis were soon sweeping southwards on a mission codenamed Operation Alaric, after the Gothic king who had invaded Rome in 410. On 9 September, Badoglio abandoned the city to its fate, fleeing down the via Tiburtina with the king ahead in a green Fiat.

The battle for Rome took place the next day at the Porta San Paolo, where Saint Paul had departed the city to walk to his death. Junior officers and civilians fought Nazi artillery in a struggle that was heroic but futile. “We have no more ammunition. Do what you can for yourselves, boys,” one officer reportedly said. For the first time, the doors of Saint Peter’s Basilica were bolted during the hours of daylight. According to the diary of an American nun, Mother Mary, ‘Blood ran in the streets.’ Up on via Veneto in the glamorous rooms of the Hotel Excelsior, the Nazi General Kurt Mälzer passed his days drinking, lunching and cavorting with women. Intoxicated by power, for nine months he would be ‘absolute master’ of Rome’s 1.5 million citizens. Men and women were accosted in the street. Nazis barged through apartment doors. People and supplies were seized, day and night. The cells of the Regina Coeli prison became a squalid waiting room for deportation and, for many, death. Writing from the wreckage, the journalist Paolo Monelli evoked Mälzer’s rule of terror: ‘he commanded, he forbade, he oppressed’.

In the summer of 1943 Pope Pius XII had rushed to the people. When four bombs fell on the Vatican in November, the people ran to him. Windows had shattered into the cupola of Saint Peter’s; the Vatican radio station was also damaged. Nazi propaganda swiftly turned the finger on ‘barbari anglo-americani’. The Roman people knew better than this. A crowd gathered in the square in front of Saint Peter’s where Pius appeared at the window of his library to hear their cries. The Germans were still in the city the following spring when Pius emerged on the balcony to a crowd of tens of thousands. Beleaguered by bombing, starvation and Nazi raids, the people had requested an audience with their pope. According to one woman there, the pope was their only sanctuary and solace as they huddled into the curve of Bernini’s colonnade: ‘German soldiers [were] patrolling the borderline, almost as if to remind us of how near we were to where that area of peace ended and the afflicted city began.’ In 1870, the new Italian king had stripped the pope of political power, seizing his capital and ending more than a millennium of papal rule. Yet by 1945, the pope was the only monarch left in Rome.

City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, its Popes, and its People is available now from Simon & Schuster.