Banksy in Buenos Aires

by Dominic Hilton

February 2023

“Call me a philistine, but I like art most when it’s good.” Dominic Hilton and friends visit a Banksy exhibition.

One thing I really hate about Buenos Aires are all the foreigners. I’m not talking about myself, of course, who came here from Britain, or about the other folks who have fled criminal regimes in their homelands. I’m talking about the tourists, who arrive in Argentina’s capital city on planet-polluting jets, only to meander through its streets looking puzzled, like they’ve been abducted by aliens then dropped here, but can’t figure out why. It’s easy to spot these visitors from the First World as they always wear baseball caps or floppy hats to protect them from the sun while lugging astronaut-size rucksacks on their backs. Every few steps, they stop to sip from fifty-dollar double-wall vacuum insulated eco-friendly leak-proof water bottles. Worst of all, because of the way I look and speak, they habitually mistake me for one of them.

Several times a day I’m forced to explain that a) I live here and b) why I live here. On the plus side, once I successfully account for myself, it also means I’ve one-upped the holidaymakers. “Oh, you naïve boobs,” I may as well be saying, “the myriad of insider secrets you hapless greenhorns will never fully understand about my beloved city!”

Of course, I don’t understand much about my city, either—but they don’t need to know that. In my defence, Buenos Aires is not an easy place to understand. Every time I think I’ve figured something out about it, I immediately realise the exact opposite is also true, and I’m back at square one, clueless as ever.

Foreigners are more predictable. When they visit Buenos Aires, they go all-in for its street art. Faces scarlet with enthusiasm and heatstroke, they’re forever setting off on the city’s official graffiti tours, then boring on about them to me whenever they get a chance. “Oh?” I say, raising an eyebrow or two. “Have you also visited the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano or the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes? The latter has a Rodin, a Van Gogh, a Goya—”

“Where?” they say, showing me yet another photo they’ve taken of some garish mural.

“It’s not that I disapprove of street art. It’s just that, to my eyes, so much of it in Buenos Aires is, for want of a better word, crap.”

It’s not that I disapprove of street art. It’s just that, to my eyes, so much of it in Buenos Aires is, for want of a better word, crap. There’s an abundance of it, too, due to the fact that artists here don’t require consent from the authorities to, say, spray paint a fifty-foot picture of an intoxicated street orphan riding a bicephalic llama onto the facade of a pricey residential building. There are a few half-decent moustachioed Frida Kahlos plastered sky-high across the city, I suppose, and I dig a good many of the fedora-sporting Carlos Gardels. The sacred murals of Diego Maradona cannot be argued with, unless you want to end up buried in one of the city’s countless mausoleums, but I could live without all the hobgoblins, Karl Marxes, and psychedelic pussies. Call me a philistine, but I like art most when it’s good.

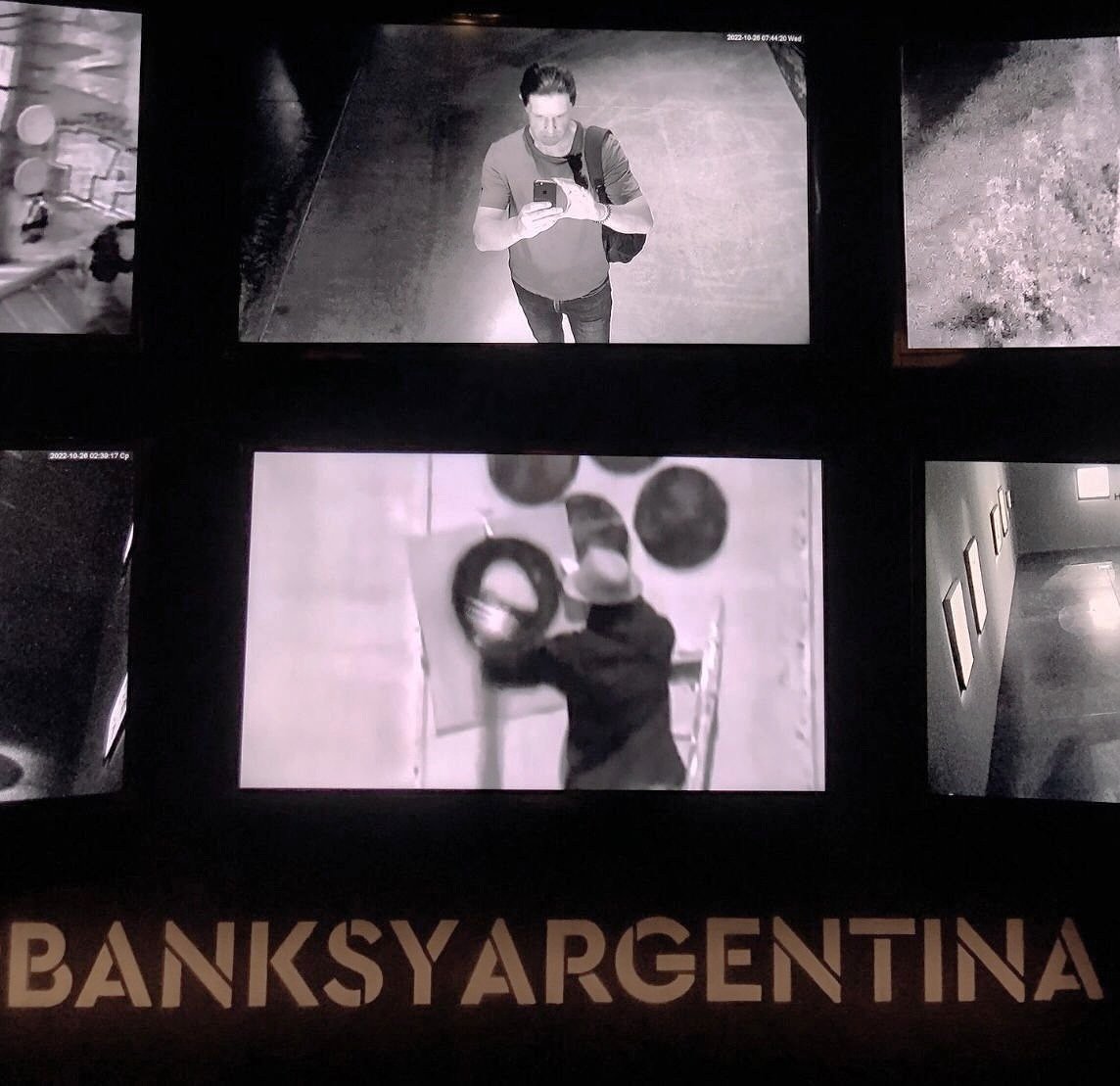

I was reflecting on all of this recently, when I visited an exhibition at La Rural in Palermo of the anonymous British street artist Banksy. The show was titled “Genius or Vandal?”, begging the question: Couldn’t he be neither? I went with two friends, Alex and Carlo. “Isn’t Banksy’s stuff on every wall in your home country?” Alex asked me.

“I don’t know,” I told him. “I don’t live there, anymore.”

We were standing next to a hollow red telephone box, reading an overwrought description of the exhibition printed in capital letters on a makeshift partition wall. “GRAPHIC CODES,” the description read, “SYMBOLIZE STRUGGLE AND RESISTANCE, TO WHICH MIGHT BE ADDED A COMPLEX, SUBCULTURAL VISUAL VOCABULARY OF A DEEPLY ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN BENT (TO WHICH BANKSY IS FULLY BOUND).”

“Forget about Banksy,” Carlo said, “I want to meet the guy who writes this shit.”

Alex had gone missing. We found him behind a velvet curtain, scowling at one of those immersive videos that play across four walls. A raggedy group of students shuffled behind us, then sat cross-legged on the floor as Carlo mumbled something about how we’d all been ripped off. I popped a fresh stick of gum into my mouth and started blowing bubbles.

“I notice you’re doing a lot of that lately,” Carlo said.

“It helps me to think,” I told him, as we moved into the next room.

“Oh, yeah? Then what do you think of this?”

Carlo pointed towards another long-winded capitalised explanation on another partition wall, this time under the heading “WHAT IS A PRINT?” The opening paragraph read: “ARTISTS INCORPORATE A PIECE OF THEIR SOUL INTO THEIR CREATIONS. OFTEN, THEY HOPE THEIR ART WILL TRAVEL THE GLOBE WITH THE AIM OF ENLIGHTENING OTHERS ABOUT THEIR CREATIVE OBJECTIVES. AN ORIGINAL DRAWING IS LIKE A MASSIVE, OLD TREE PLANTED FIMLY IN THE GROUND, AND PRINTS ARE LIKE FERTILE SEEDS BEING CARRIED AWAY BY THE WIND, TRAVELING GREAT DISTANCES, LOOKING FOR A NEW PLACE TO TAKE ROOT.”

I laughed out loud. Then I turned to look at one of the prints. It showed three Red Army tanks entering Tiananmen Square. A lone figure courageously stood before them, advertising a golf sale. I laughed out loud at that, too—though this time because it was excellent.

Alex was ogling a briefcase full of £10 banknotes in which the Queen’s image had been replaced with Diana, Princess of Wales. I stole up behind him, recalling an encounter I’d had the week before in barrio Retiro. Carlo and I had been to the Museo Latinamericano, and afterward we stopped for coffee on Calle Arroyo. We were discussing the state of the museum’s bathrooms, when a wispy-haired Argentine gentleman in three-piece tweeds approached our table. The moment he cleared his throat, adjusting his huge square-framed spectacles, I knew what was about to happen and racked my brain for an excuse to escape. “You’re English!” the stranger announced, right on cue. “I can’t help admiring your accent.”

“Years of training,” I said, hunched over my espresso.

The man noisily dragged a chair across the paving stones, joining us at our table, uninvited. Carlo stared at him, then shook his head and began listening to the messages on his phone. The man never introduced himself or asked who we were. He simply talked at me for half an hour, giving me his resumé, which I definitely hadn’t requested. “I’m the descendant of a Scottish marquis,” he insisted. Then he asked me what I thought about the Queen dying, before claiming to have been related to her.

“You’re royal?”

He waved his cigarette in my face. “Elizabeth was a distant second cousin, or something of that sort.”

Before I could blink, he moved onto the subject of Charles and Diana, who he claimed to have met in Argentina.

“Together?” I asked.

He chortled self-importantly. “I’m not sure that’s what you’d call it. Diana confided in me that Charles was being unfaithful, but she was insistent that I never tell anyone.”

“You just told me.”

“Well, it hardly matters now, does it? She’s dead and he’s King.”

“She’s dead?!” I shrieked, but either he didn’t hear me, or he didn’t understand. Instead, he stood up, adjusted his crested necktie, and wandered away.

Carlo put down his phone. Two mothers who were nursing new-borns on either side of our table took a moment to express their disbelief, apologising to me on behalf of their countrymen. I told them there was no need to explain, that I was perfectly used to it, which was the truth.

“While we’re here, do either of you have any names you’d like to drop?” Carlo asked them. “Were you once BFFs with Michael Jackson? Because I used to know Julius Caesar. Called him Julie. You know the Colosseum in Rome? That was my idea.”

Ten minutes later, the man in tweeds suddenly reappeared, like a phantom in a Victorian ghost story. This time, he took a seat at a nearby table, from where he loudly expressed his feelings about Boris Johnson, who he called “a demagogue, like Vladimir Putin.” Then he started in on Donald Trump, whom he “used to know intimately.”

“Of course you did,” I said wearily, before dropping a few thousand pesos on the table and getting the hell out of there.

The final room at the Banksy exhibition was roped off for a “Virtual Reality Experience”. Security guards ushered us inside, then sat us on glossy white stools and tenderly attached our headsets. It was my first time and I’d absolutely no idea what to expect. My heart started to race as I swooped above the empty streets of London past noisy bin lorries, scurrying rats, and countless examples of Banksy’s unmistakable artwork. I turned around and was amazed to discover that the virtual landscape was 360 degrees; that there was no way out.

“Jesus Christ!” I shouted.

I felt Carlo’s hand squeeze my thigh. “Calma,” he said. “You’re making a scene.”

When the ominous experience finally came to an end, the stealthy staff removed our headsets, and Carlo slapped my chest. “Check that out!”

I followed his gaze. Across the room from us a woman was taking a selfie while wearing her headset.

“That’s the most Banksy thing I’ve seen all day,” Carlo said, taking a photograph of her struggling to take a photograph of herself.

Alex had gone missing again. We found him outside, staring up at the sun. “That shit gave me vertigo,” he explained. “I thought I was going to throw up.”

“In real life?” Carlo asked.

We walked to a local café, which was buzzing with gorgeous porteños tucking into pastries and pancakes. As we sat there, I found myself wishing, not for the first time, that I was a visual artist, instead of a writer. I thought about some of the rambling jokes I could condense into graphic form, as well as all the fast ones I could pull on an adoring, credulous public. Like the Banksy baseball caps and T-shirts on sale in the gift shop at La Rural. They’d been mass-produced and emblazoned with the slogan DESTROY CAPITALISM. I’d taken photos of them with my iPhone, wondering whether or not the joke was on me. Did the branded apparel represent some sort of reverse irony, or did oblivious anti-capitalists really buy these items and wear them to riots? Only Banksy knew for sure, and I wasn’t in any position to ask him.

“Banksy is probably a genius,” Alex said, unscrewing his plastic bottle of mineral water, “although I also like him as a vandal.”

I shrugged, remembering Banksy’s unhelpful words: “People either love me or they hate me or they don’t really care.”

“He’s like Starbucks,” Carlo said, “but with a brain.”

“Exactly,” Alex said, a little unsurely.

A woman somewhere in the café let out an earsplitting laugh which went right through me. Carlo tapped his tiny spoon against his espresso cup. “As for all the DESTROY CAPITALISM stuff,” he continued, “I really don’t know. Take a look around this place. You ask me, capitalism is just there. It’s not capitalism’s fault if someone chooses to take a thousand photos of avocado toast on their iPhone 14 Pro Max. I’ve had the same shitty phone for years, and I don’t give a fuck what anyone thinks about that.” He grinned at our favourite waiter, Joey, who was loitering behind my chair. “Plus, I’ve never once ordered avocado toast, let alone taken a photo of it. Is it good?”

“It’s great,” said Joey.

“It depends,” Alex said. “If you like avocado and you like toast, then yes, it’s not bad.”

Joey sighed, and we fell into a thoughtful silence, eyeballing an adjacent table. Four American tourists were tucking into loaded plates of Instagrammable avocado toast. Their giant rucksacks had been propped up against the cushions and three of them were wearing baseball caps advertising high-priced universities. Soon enough, the blondest one pulled an iPhone Pro out of her bra, held it high above the table, and started snapping away.

Banksy: Genius or Vandal? La Rural, Buenos Aires, Agosto 26, 2022 - Diciembre 14, 2022