'It is the living we should fear'

by ASH Smyth

November 2023

ASH Smyth reviews Chats with the Dead, as Covid-19 fans out across Asia.

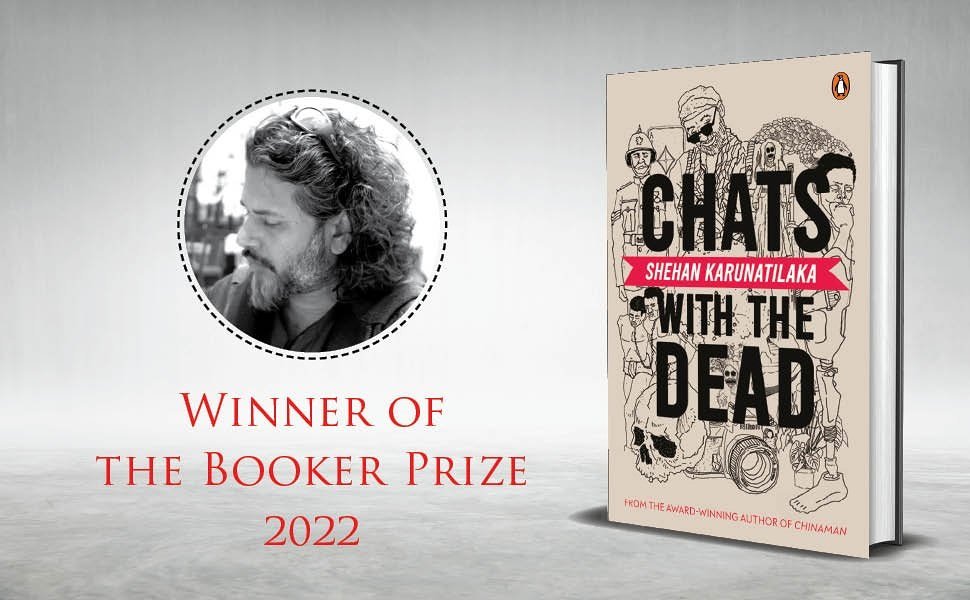

In 2010 I reviewed Shehan Karunatilaka's debut novel, Chinaman, for the Sri Lankan Sunday Times.

Although it had, already, won the Gratiaen Prize (in manuscript), this was, in fact, the book’s first review anywhere. And it was brilliant, I said: everyone should buy it—pausing to note, for form's sake, that I’d helped proofread the final version, and hoping (in the rather small world of Sri Lankan English letters) this would not come across as either cause or symptom of some hopeless bias.

A decade on, that situation had only got worse. In 2014 Karunatilaka and I became related (wife's cousin's cousins... we are fairly confident); and betweentimes, Chinaman had gone from strength to strength. It won a raft of prizes (Commonwealth, DSC Asia), had been or was still being translated into several languages (including Sinhala), and in 2019 year a Wisden panel voted it—a quite absurd achievement, this—the greatest cricket novel and second-greatest cricket book of any kind of all time. Its umpteenth printing soon appeared, from Penguin India, in a '10th Anniversary' special edition: hardly standard practice for even the most successful novels.

Meanwhile, Karunatilaka had not been resting on his laurels. All jokes aside about the difficult second album/novel (and he’d have been equally happy with either, I suspected), he’d already published his first children's book (Please Don't Put That in Your Mouth) and written its follow-up; there was more-than-casual talk of a short-story collection; and there was the somewhat unexpected matter of a forthcoming cookery book—a co-project with his designer wife.

Chats with the Dead is the story of Maali Almeida, a 34-year-old photographer who's good at 'winning at blackjack, seducing young peasants, and photographing scary places.' Or rather was – because he's dead now.

It's Sri Lanka, 1989, and Maali had been in bed, photographically-speaking, with a lot of the conflicting parties, not to mention their agendas. Communist insurgents, the government, the BBC, a Tamil-rights group; he has been to the frontlines for all of them. To say he was 'promiscuous' would strike, well... exactly the right tone. And in a box he keeps of his disturbing/unpublishable outtakes, he even has a photo of his killer—'the chances of liberating [which] are as likely as Lanka winning a World Cup.' He just can't remember who it was yet: whereby, our detective story. 'It is funny and unfunny what your brain chooses to retain.'

He had also been in bed, non-photographically-speaking, with, among others, his girlfriend Jaki and his boyfriend DD— a love triangle whose sides don't meet (based loosely on the life of activist actor and journalist Richard de Zoysa). These two are also cousins, because, y'know, Sri Lanka.

Maali now finds himself in some form of the afterlife—though quite which he is yet to fathom. This is a busy place (as Nietzsche once put it, the living are only a very small subset of the dead), and by and by he crosses paths with a dead lawyer, a dead bodyguard, two dead lovers... some helpful, others vengeful, a few competing for his soul, and most of them frustratedly trying to chat back with the living.

So now he has to learn 'the rules', as well as solve the mystery of his murder. It’s the Mahavamsa meets The Matrix... in a South Asian government department.

“By page 16 Maali is now watching his own corpse being incompetently disposed of by paramilitary goons.”

'When you fantasized about heaven you thought you'd be greeted by Elvis or Oscar Wilde. Not by a dead doctor. Or a deceased Marxist.' But by page 16 Maali has met both, and is now watching his own corpse being incompetently disposed of by paramilitary goons, at Colombo’s rank, green Beira Lake. And while he talks thus, retrospectively, to himself (the whole thing's in the second person), there swirls around him an all-comers spirit realm of fanged ghouls, minor deities, baby-stealers, charms, seances, sorcery, urban legends, prayers, dreams and talking animals, an inventive theological mix of everything from a rejected queen’s curse to the Crow Man in his urban underpass.

There exists already a Karunatilaka style, and here it is in spades: dive bars, Colombo culture, books, art and (particularly) music, the things that are—and are not—talked about. His taunting games with names and places. A cheeky drop-in from the leading men in Chinaman. A page-long parody of Anil's Ghost? And then the storyteller's signs deployed by every shifty author from Herodotus to Ondaatje—'All stories are recycled, and all stories are unfair'—the whole lot strung together with the now-familiar mischievous logic, verbal levity and seamy humour that mark him out as a Sri Lankan counterpart to, say, 2015’s Booker-winner Marlon James.

As with James, this doesn't always make for pleasant reading (consider Maali's job); but then his thoughts on all those easier alternatives might well be coded in the line, 'Monsoons and full moons make all creatures stupid.'

Chats with the Dead is considerably more direct in its satire than was its predecessor. Besides, the stakes are higher. The abject slavery of many lives; the rank iniquities of much religion; the dreadful suicide rate. And as he picks at these scabs of SL's less-than-savoury history, Maali's most unflattering (and generally unchallenged) remarks are reserved for the nature of the post-Independence nation: as a corrupted paradise, on its political class, and on its tendencies to violence. 'Yakas [devils] are made, not born,' someone admonishes. It's not conciliatory, nor is it all that optimistic. Karunatilaka—I mean, Maali...—has a savagely critical reading of the self-conscious national lust for a rapacious origin story.

Reflecting on the spurious leonine self-image of his countrymen, Maali reflects that 'if we must have a national creature, if it must be on our flags, in our myths, and painted on our sports teams, why must it be the clichéd lion? If we must have an animal as a national symbol, let it be something original that we can own.'

'Like many Sri Lankans,' he goes on, 'pangolins...'—but I shan't spoil it for you. Needless to say [Covid now bursting forth across the world], the month or so since Chats's launch has seen you-couldn't-make-it-up connections twixt the pangolin, Sri Lanka, and the realms of death and afterlife.

Chats is an entirely successful and fully mature novel, as good as—albeit much darker and less full of, well... life than—Chinaman. But it's not perfect. Too many variants of 'Maali', 'malli', 'Maal', 'Malin', and so on for the untrained eye/ear; some minor characters who might be given clearer edges (or got rid of/merged); some textual messiness; an anachronism or two; a couple of vague inconsistencies, and one hell of what seemed like a twist (read literally), just pages from the end… which turned out to be two sentences in need of much more careful separation. A lot, frankly, that ought to have been dealt with by a world-bestriding joint like Penguin India.

“But the bigger problem, I fear, will be one of international 'accessibility'.”

But the bigger problem, I fear, will be one of international 'accessibility'. In my review of Chinaman I said I thought the quite heavy preponderance of little-known Sri Lankan terms and Singlish might end up denting its saleability. The international success of that book would suggest that I was wrong—or that assiduous changes were made during the foreign publication process.

The same applies here. Minor matters of vocab or narrowly-regional reference (a sharp remark about shop signs 'that end in consonants', e.g.) can of course be edited; but in the case of Chats, the hardwired very-Lankan-ness—the '80s politics, the social concepts and the mytho-religious lexicon: the meat and bone of the matter, if one can use that term for ghosts—is perhaps much more pervasive than the native reader might appreciate. Sri Lankans may enjoy the novel (doubtless the wrong word) for a certain grim nostalgia quotient; but all but very-interested foreign readers will, I think, conclude that there is rather a lot 'going on'.

So much for second novels, difficult or otherwise. In literature, as in all else, people are ingrates—so it's quite likely this will not be greeted with the fanfare that met Chinaman. For better or worse, Chats with the Dead is now a novel by a multi-award-winning author, which will be judged on more than its own merits, and/or held to a higher, harsher, standard.

More locally, the book may yet prove to have landed in a timely fashion. In these increasingly apocalyptic times, let us hope Maali Almeida is wrong when he warns: 'Do not be afraid of ghosts, it is the living we should fear.'

A version of this article was published in the Sri Lankan Sunday Times, March 2020.

Tune in tomorrow for Richard Simon’s 2023 assessment of how Shehan Karunatilaka’s Chats with the Dead became Booker Prize winner The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida.