All I Want for Christmas is... Books!

by The Emigre

December 2023

Updated daily from December 1 through to December 24, The Emigre presents an alternative Advent calendar of books our writers would be happy to receive for Christmas.

December 24

Here’s an eminently reasonable and not-at-all last-minute Christmas wish, I think you’ll agree.

So that I can have some time off with the kids from, say, now til January, maybe Santa could deliver the first draft of my next novel? That’d be handy, right (if somewhat spooky… and unforgivably lazy)? Frankly, I’d settle for a tight 2-page synopsis—or even a loose 10-page one. If only someone would invent a machine where you just enter garbled thoughts and receive pristine prose in return. Someone should!

Humouring the hypotheticals for a moment—and assuming Saint Nick has access to that great library in the sky containing every unpublished, unwritten and unthought-of book in the cosmiverse (is that Borges? Or Sandman?)—I suppose I could ask for all the deleted scenes from the Bible; the completed Edwin Drood; the final Game of Thrones instalment; the collected works of Kilgore Trout; the unpublished novels that JD Salinger allegedly dropped into safe deposit boxes every fall; or Wikileaks: The Complete Cliffs Notes (#FreeAssange, if anyone’s listening).

But if absolutely required to stick to finished, published books? Maybe one of William Goldman’s out-of-print early novels? A full set of Alfred Hitchcock and The Three Investigators mysteries (1974-78 covers only please)? Or that Agatha Christie book which an evil Aunty once ‘borrowed’ from a teenage me, the one that invented the slasher horror genre, the one with the dead golliwogs and the N-word on the cover...?

Tell you what, Santa: just for you, I’ll keep this simple and achievable (a good tip for New Year’s resolutions, and a pro-tip for life). Last year, I asked for Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano, and got an anniversary edition from the great man’s kind estate! This year, I’d be happy with either God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (which I didn’t know existed as a novel until a few months ago); or a 1987 hardback of Bluebeard, one of Von’s three latter-day masterpieces (according to me), which I have previously savoured on audio, but do not own as a tactile on my shelf.

Still, though: if the collected works of Kilgore Trout did exist, or if even the slimmest novella by Vonnegut’s notoriously-unsuccessful alter ego were ever to make it into print, I’d just be blown away to find that in my stocking. Ideally this one, thank you:

“Kilgore Trout once wrote a short story which was a dialogue between two pieces of yeast. They were discussing the possible purposes of life as they ate sugar and suffocated in their own excrement. Because of their limited intelligence, they never came close to guessing that they were making champagne.”

Merry Christmas and happy reading, y’all!

— Shehan Karunatilaka won the 2022 Booker Prize for his novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida.

December 23

I love a signed book. And the more elegant the signature, the happier I am. Kazuo Ishiguro’s is a calligraphic delight. At the opposite extreme, Rachel Cusk’s looks like a couple of wavering beats from someone’s failing heart on a hospital monitor.

So, the real question for me when choosing this imaginary Christmas present is, whose signature have I not got? Maybe a Nabokov (either Speak Memory or Lolita)? Or a Vonnegut (God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, or the super-obvious one)?

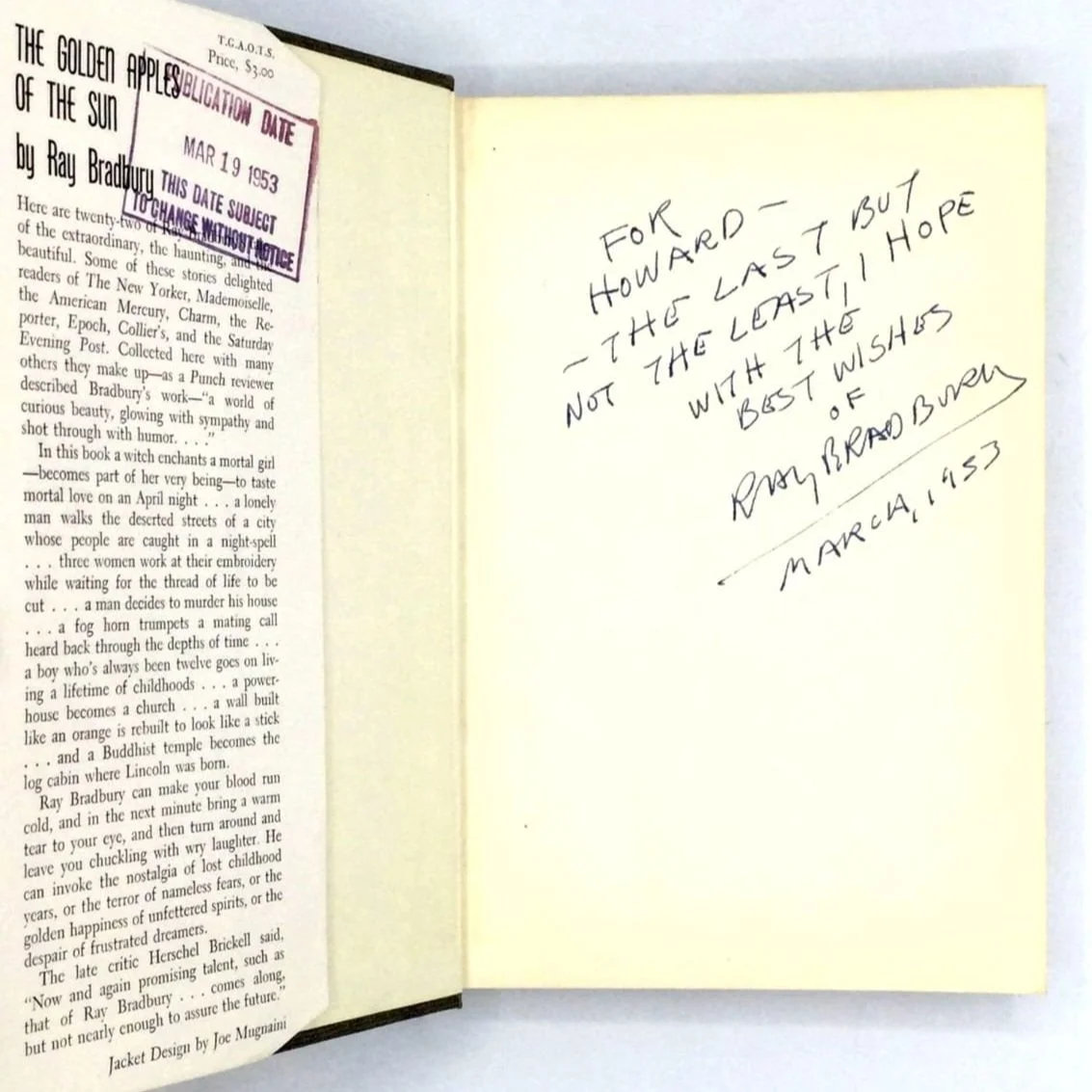

After some rumination, though, teenage nostalgia wins the day. For nothing could be more thrilling to own than a signed first edition of Ray Bradbury’s The Golden Apples of the Sun. It was my first Bradbury, prompted solely by the revelation that one of its stories—‘A Sound of Thunder’, about big-game hunters from the future travelling back in time to take down a Tyrannosaurus Rex—gave my teenage pop hero Marc Bolan the name for his band.

But having got through that collection in about two days, I had to have more. Previously I’d been a slow and almost reluctant reader, so this immersive joy was wholly new to me. Quickly exhausting the local library’s supply of Bradburys, I resorted to stealing The October Country and I Sing the Body Electric! from Heffers bookshop. It was my mother’s fault. She kept telling me to make these books last, as if they were chocolate bars rather than the beginning of an entire education. Even at 14, this struck me as somewhat short-sighted.

Fully immersed, now, in the fantasy of owning this autographed first ed. of The Golden Apples, I turn to eBay. And what a beautiful thing it is! A gorgeous yellow and grey cover, with a pleasingly naïve line drawing of an eye that’s also both a sun and moon. How much would the hypothetical generous soul who gave me this gift have to part with? Well, obviously I'd want the most expensive copy, so I click on the one selling for an eye-popping £2444.54 (what’s the 54p about?!). I’m also curious to see if Bradbury was an Ishiguro or a Cusk, so I check the seller’s photo of the signature.

Now: if you’ve read any of my other pieces for this august journal, you’ll know I’m something of a connoisseur of the coincidence. I therefore can’t quite believe my eyes when they fall upon the following inscription":

My name isn’t all that common. That’s to say, I know at least a dozen Nicks, but not a single other Howard. And what’s my wife’s name doing right there under Bradbury’s??

It takes a moment to realise that 'Marcia', here, must be a place. A quick google confirms that it’s some ghost town in the USA, not far from Roswell. So now I’m thinking about Ray Bradbury, driving across New Mexico, and the connotations of that particular scenario. In fact, I think I feel a little story of my own coming on...

— Howard Male is the author of a quartet of genre-defying novels.

December 22

Through the ether from far austral lands (with apologies to the shade of Alfred Austin), came the invitation for a ‘couple of paragraphs… about the single volume you’d want out of all printed history…’ An invitation to give my opinion? When have I ever turned down such an offer? My acquaintances, friends and immediate family (especially the last) could not conceive of a refusal.

I read further. I was permitted to select only one book—but that stricture could be taken to include things that had never existed, except in my literary cupidity. I could invent, rearrange, twist, ‘massage’. I was giddy at the prospect. The Editors had granted me a Wand of Power!

Might we, I mused, have a comprehensible novel by Henry James? What if Keats went on to live as long as Wordsworth? Why shouldn’t H. H. Munro, one of the most elegant stylists in modern English, be spared the sniper’s bullet in November 1916, and write another 40 years’ of Saki stories (as well as being spared his grim last words of “Put that bloody cigarette out!”). On that same theme, could Edward Thomas, please, please, come back safe from France?

Should this even be confined to literature, in fact? Imagine, if you will, that I have just finished reviewing Mozart’s final opera, Addio il Mondo, written when he was 88 and—despite the title—still full of young, fresh energy. And now at least we know where he was buried!

My wild hallucinations were brought back down to earth by recollection of the ‘single volume’ business. Well, I have two [Ahem—Eds.].

The Leisure of an Egyptian Official by Lord Edward Cecil is of its time; but gloriously written. Ned Cecil was known as one of the wittiest of the Salisbury Cecils—some reputation—who sadly coughed his lungs out at a Swiss sanitorium aged 52 (and please may I go back and change that? [Wand privileges revoked!]). My grandfather served with Cecil, and always said that Leisure… captured the life of a colonial official to perfection. It was one of his favourite books.

My second is James Woodforde’s Diary of a Country Parson:1758-1802. A wonderful, unselfconscious chronicle of the slow turn of eighteenth-century country life. Some gargantuan meals, carefully itemised; vignettes of rural events, as when his Piggs (sic) get drunk on home-brewed ale; and deadpan asides, such as:

February 16th, 1763: I dined at the Chaplain’s table…upon a roasted Tongue and Udder. N.B. I shall not dine on a roasted Tongue and Udder again very soon.

This last has become part of our family vocabulary when recalling unexpectedly horrible food. I pray the Lisvane table will see no such culinary atrocity, in this—or any other—festive season.

— Lord Lisvane is a British life peer who served as Clerk of the House of Commons.

December 21

What book would I chose from all recorded literary history? Well, a first edition of the Bible or one of the missing Aeschylus playscripts would be nice.

But of all the books that exist, it would be the manuscript of Middlemarch, as sent to the printers, then returned to Mary Ann Evans—a.k.a. George Eliot—who had it bound and presented it to George Henry Lewes, the man she loved and lived with but was never able to marry. After Lewes's death, the manuscript came back to Evans/Eliot; and when she died, it passed to Lewes’s eldest son Charles. After his death, in 1891, it was entrusted to the British Museum, where, I presume, it still safely resides. Perhaps it's moved on to the British Library. In any event, Reader, I do not have it!

I first fell in love with Middlemarch and its author in 1981, discovering her bold opinions and unorthodox life, and her extraordinary appeal. How else is it possible that Queen Victoria and Edward, Prince of Wales, could both be huge fans?

To be honest, my expectations had been low. Unaccountably, since it was a book my mother loved—and one which has been adapted for primetime TV at least twice—I absolutely hated The Mill on the Floss. (I probably still do, but can’t bring myself to re-read it.)

But setting out for a Long Vacation Interrailing holiday around Italy, and faced with the trade-off between clothes and books, I decided to stock up on orange-spined Penguin Classic paperbacks of Victorian doorstoppers: Bleak House, something by Trollope, the title of which now eludes me, and Eliot's masterpiece.

Somewhere between Urbino and Florence, I opened the last of these, and fell in love at once with Dorothea Brooke. Fierce in her own skin, burning with intellectual fervour, abrim with the wish to learn and grow and make a difference. Looking back on it now, yes, we may have shared a slightly sanctimonious sense of our own rightness, a belief in our own judgement and a readiness to judge others... But how, as a 20-year-old self-declared feminist, could I not love her and her creator, both of them determined not to be defined by gender and upbringing, butting up against the expectations of a woman’s life, place and preoccupations in provincial C19th England?

Middlemarch is not a book that paints great deeds and big achievements, but there is a lot of life and quiet heroism in it, as Dorothea and those around her go about their lives, making choices, or having 'choices' forced upon them, and reaching accommodations along the way with the consequences of their own and others’ actions.

It's a book full of sadness and spoiled hopes, early promise and idealism worn down. But it is still a glorious story about the importance of small acts of kindness, of living the best life you can. And it is told by an extraordinary woman, growing and questioning, engaging with radical views at home and from the Continent, and making her own way in the world, setting aside stuffy mid-Victorian propriety, living in an—ahem—'unconventional' household with George Lewes and his wife, and writing, writing, writing. Fiction, non-fiction, editing work and translations poured from her pen throughout the middle decades of the turbulent century, amidst the social and political ferment and revolution shaping the world and the lives of those who populate her novels.

Mary Ann/George died, aged 61, in 1880, and was buried not in Westminster Abbey but in Highgate, beside her friends, the leading social challengers and political and religious dissenters of the era, and close, forever, to George Lewes.

Older now than George Eliot was when she died, and certainly more acquainted with grief, sorrow and regret than I was at 20, revisiting her magnum opus on my Kindle I confess that I am, in my heart of hearts, hoping that Santa (who can do anything, right?) might pop, if not the manuscript, then at least a signed copy of Middlemarch into my Christmas stocking.

— Her Excellency Alison Blake CMG is Governor of the Falkland Islands and Commissioner of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

December 20

I love used bookstores, especially those maze-like ones where overstuffed shelves and towering stacks of books threaten to spill over on you at any second.

And some books are simply better second-hand. Who wants a nice, neatly-packaged Jim Thompson novel with a tastefully-designed modern cover when you can have one with a cracked spine, lurid art, and bold letters declaring "A NOVEL OF MURDER UNLIKE ANY YOU'VE EVER READ"? That book has seen some things.

But what I especially enjoy is finding dedications: the romantic gesture that didn't pan out, the graduation gift—something that gives that individual volume a little history, unique to itself. Once I picked up a copy of Yehuda Amichai's poetry which was inscribed: "Dear Philip! On your 14th year. This book was written by the poet laureate of Israel, who went to elementary school with me in Nazi Germany. Read it when you feel like it, a bit at a time." It was dated April 1997, making the Philip it was dedicated to about my age.

So, this Christmas, I'd like a book—any book, really—that tells a little of its own story, a book that bears the marks of other hands, maybe an underlining or two, or notes in the margins. A book which reminds me that books are always more than just the data inside, more than the sequence of characters and empty spaces, but physical objects, interacting with us in space and over time, accruing their own lives and the whisperings of lives past.

— Phil Klay is a former US Marine Corps officer, and winner of the National Book Award.

December 19

If I could have any volume ever published ever, I think it would eventually come down to an impossible choice between The Book of Kells—how great would that be to have on your coffee table??—and Karl Marx’s personal copy of Laurence Sterne’s The Life & Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, the brilliant 18th century anti-novel about the literal impossibility of writing a novel.

Since I see The Book of Kells has already been dibsed [see below, December 10—Eds.], I guess that means I’m left with Tristram Shandy!

It’s not just the mind-boggling unlikelihood that the totally zany Shandy was the favourite book of Marx, the father of dialectical materialism and arguably the grandfather of some of the worst genocides of the 20th century. It’s also that over the years I’ve adapted both Tristram Shandy and The Communist Manifesto as comic books, and found their authors’ ghosts to be enormously amiable collaborators.

Being able to hold Karl Marx’s copy and read his (inevitable) marginal notes would further cement what has to be the weirdest cross-time potential double act in history.

— Martin Rowson is a multi-award winning cartoonist, illustrator, writer, graphic novelist, broadcaster, ranter and poet.

December 18

I once went on a date where my prospective paramour spent over half an hour explaining the difference between a code and a cipher to me. This was despite the fact that he should have been able to tell at a glance that I have read The Code Book by Simon Singh (twice), and visited Bletchley Park of my own volition and would like to go again.

Both the explanation and the date were tedious. So tedious that I am not even going to attempt a recap here: that is for you to google in your own sweet time, should you be inclined. But the moral of this story is that similar interests do not always mean similar levels of interest—and also that you shouldn’t really spend any part of a first date in lengthy exposition, lest you expose yourself as someone impervious to every social indicator that the person opposite is mentally planning how best to murder you and dispose of your body without getting caught. These little things do matter.

Despite this, the book I most want for Christmas this year is one that has long fixated codebreakers, cryptographers, historians and all sorts of conspiracy theorists: the Voynich Manuscript. A beautifully illustrated codex, on vellum carbon-dated to the early 15th century, it is written in a totally unknown script. And so, to be more specific: I do not want the Voynich Manuscript. I want a translation. Into English, preferably.

What might this extraordinary document tell us, if we understood it?

Theories range from it being a mere hoax to a full-blown code, or perhaps the sole surviving instance of some natural language. We can dismiss the hoax theory as being constructed by the sorts of people who take pride in demonstrating to others how a magic trick has been done, right there in the middle of the show whilst the glamorous assistant is still shaking glitter from her hair. And I’m not good at languages (see below). So I want it to be a code, and I want it to be broken, and for me to be provided with the only available translation.

I cannot do this myself, you understand. I’ve read about Champollion’s labours on the Rosetta Stone, and to be honest it sounds like something I won’t be able to fit in after work (especially as he cheated by having two already-decipherable languages on hand to aid his hieroglyphic translations). No, someone with more time needs to take this on—ideally out of undying (but non-creepy) devotion to me.

Once I have my translation I shall consider my next move. Given the flora and fauna illustrated alongside the text I will almost certainly hold in my hands the key to a pharmacopeia more powerful than any the world has seen and/or a map to where those dragons actually do be. Both will of course prove hugely beneficial to humanity in general and so I will (probably) consider issuing them under licence, for a range of carefully-calibrated but entirely-reasonable fees (Ts&Cs apply).

And if said translation can’t be made available before December 25th? Well, in that case I’ll take a first edition of The Iliad. Y’know, the one that kid gave J-Lo in that dreadful movie.

— Becky Clark is a former policy officer with English Heritage.

December 17

What I want for Christmas is my copy of Angela Carter’s Wise Children back from G___ S___, to whom I lent it and who still has it. It’s neither a fancy nor first edition, just a serviceable Vintage Classic with Nora and Dora silhouetted in their dancing girl avatars on a hot pink cover. My friend, who lacks most other blatant moral failings, claims it was returned to me—which it wasn't.

It's a novel I like to have around, even when I’m not re-reading it. I like to write a pedantic work email and then open the novel at random to listen in on Dora punning her way through her life story. She’s generally sauced-up beyond reason, and the chances are high that it’ll open on some soppy Shakespearean reference or Toast of London antecedent.

Who wouldn’t want for Christmas a perfectly selected book? Recent gifts from my family, who love me very much, include The Discomfort of Evening (‘I asked God if He please couldn’t take my brother Matthies instead of my rabbit’) from my sister, and John Healy’s memoir The Grass Arena from my dad (back blurb: ‘When not united in their common aim of acquiring alcohol, winos sometimes murdered one another over prostitutes or a bottle’).

Returning Wise Children to the spot on the shelf that I’ve kept mournfully clean would be the lost sheep returned to its fold. And at Christmas too! Its chaotic family reunions have the smack of Planes, Trains and Automobiles (which came out three and a bit years before the novel was published—I bet Carter’d watched it), and its story ends like a luxury cracker, when after much pulling and groaning there comes the most fantastic bang.

— Nathan Koblintz writes poetry among family and small animals in Colombo.

December 16

All I want for Christmas—beyond all the other things I want which, invariably, once I have them in my hands, cease to interest me anymore because I have them now, whatever or whoever they may be, and thus the wanting that sustained me, excited me, has been rendered obsolete, so I just feel empty, questioning whether I ever wanted that thing in the first place, whether I’ve ever actually wanted anything at all, or did I just think I did, or force myself to think I did, because that was better than accepting that a healthy desire for things and stuff (big or small, physical or otherwise) has forever escaped me, which means there’s a chance I’m not alive, or maybe I’m incredibly sad, or perhaps I’m totally enlightened, having fallen into some kind of bleak nirvana that I can’t climb out of—anyway, all I want for Christmas is a hardback copy of Andrew Durbin’s 2020 book Skyland, a short autofiction thing about a young man who spends ten days or so of a scorching August hopping across a load of Greek islands in search of a painting of Hervé Guibert, and maybe also himself. A salt-scented little book full of gorgeous ekphrasis and ‘wait what the fuck’ moments. A book which functions, to look at the bigger picture, as a succinct and deeply poignant presentation of a terminal world. A world unravelling itself, just as those who are condemned to inhabit its increasingly hostile atmosphere are unravelling themselves in turn.

Andrew Durbin is a friend of mine, which makes the experience of rereading his work, which I’ve done many times now, all the more uncanny. I want to sit in my apartment alone on Christmas Day and read that book from start to finish, then make my way through a good bottle of vodka with some good Spanish ice in a glass, and fall asleep in my living room surrounded by all the paintings the owner left, including a copy of ‘The Surrender of Granada’ by Francisco Pradilla Ortiz, a painting that takes up the entire back wall, a painting I stare at each day, and try to imagine what it must have been like: to return home after all those years. Try to imagine if home could ever feel like home again. Then I want to fall asleep and stay asleep without dreaming, without a single horrendous image flashing like headlights on the back of my eyes, then wake up and go to the freezing mountains outside Madrid with my dear friends and lose my hangover somewhere between the car and the restaurant we’ll walk to, where I’ll order a beer and a calamari sandwich before the sun goes down again, and the world treads on despite itself, until next Christmas, wherever we’ll be.

— George Sebastian is a writer based in Madrid.

December 15

In the second chapter of Dostoyevsky’s The Double, the protagonist, Yakov Petrovitch Golyadkin, is told by his doctor to seek ‘Entertainment…and, well, friends’, not to ‘be hostile to the bottle; and likewise keep cheerful company.’ Such festivity, Dr Krestyan Ivanovitch declares, will cure Golyadkin of a character so anti-social that it now threatens his life. Golyadkin is horrified. He bursts into tears, blurts out an account of his many enemies and flees the office of the physician, declaring him ‘stupid as a post’.

In this season of seemingly unceasing social events, I can think of no better cure than an evening alone with a gifted copy of The Double, a novella on the will, society and insanity set in the stifling social atmosphere of nineteenth-century St Petersburg. For some (me), the parties of December demand a forced merriment akin to what Dr Ivanovitch describes as ‘a break in your character’. I can sympathise with Golyadkin, a deeply awkward government clerk, and his alarm on receiving the prescription: party time.

Regrettably, I can also sympathise with his experience when he takes his ‘medicine’ by attending a ball. Once there, Golyadkin is both vindicated and humiliated as he tries and fails to ‘appear jaunty and free and easy’. Eventually, two servants usher him to the door and he runs off into the night.

After this painfully evocative account of social agony, the novella becomes an increasingly immersive description of Golyadkin’s spiral into utter psychological turmoil. Plagued by a doppelgänger far more erudite, socially lubricated and professionally successful than him, Golyadkin loses his dignity, servant and marbles, as the Double destroys his life. This is part of the narrative that—I hope—most readers will find far removed from their own reality. Yet by the end of the story, all will be steeped in vitriol for the odious, smarmy Double—and confused about whether he ever existed outside of Golyadkin’s troubled mind.

On reflection, The Double might have you reaching for the bottle after all. Yet unlike much enforced ‘cheerful company’ this psychological portrait is truly engrossing. It is, as Nabokov judged it, ‘a perfect work of art’, and, thankfully, one that can be enjoyed at home, alone.

— Jessica Wärnberg is a historian and author of City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, Its Popes, and Its People.

December 14

For Christmas, I want the first edition of The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran, Prophet, Madman, Wanderer, published in earlier forms between 1918 and 1932.

At year's end it's always sobering to consider what you did well, and badly, with an eye to change come next year.

Kahlil is full of timeless wisdom on being everything from a friend, to a parent, to a lover.

— David Smith, an award-winning correspondent for ITN/C4News, now writes from South America.

December 13

At this time of year the imagination drifts back to the landscape of Iceland, last seen from a touring bus six years ago: gently steaming lava fields, candles in cottage windows, and clusters of pink, white and blue lights in snowy roadside cemeteries.

The wintry Norse traditions are of course not only picturesque but in many cases satisfyingly robust. The huge Yule Cat, of course, that roams the countryside and devours any children spotted without new clothes (a kind of double whammy: no new clothes, and to top it all you get eaten by the Jólakötturinn!), the rather twisty reasoning being that good children who do their chores are rewarded with spanking new outfits and so at the same time spared these feline depredations. Then there are the thirteen Yule Lads—Jólasvenar—who come to town one at a time in the run-up to the winter solstice, leaving gifts (good) or rotten potatoes (bad) on window-sills. Which is nothing, compared to their terrifying mother Grýla, who inevitably boils misbehaving children up in a huge pot.

It's the memory of those lights that haunts, though, that strange, volcanic landscape and the proper straight-to-the bone cold. That’s why, for Christmas, I would like a collection of Icelandic sagas—parallel text if possible—not to read the whole thing in Old Norse (don’t be ridiculous), just to spot and decipher the odd word or phrase.

These sagas, first committed to calfskin in around 1200, are highly structured narratives with an array of often recurring characters: Ketil Trout and his father Hallbjörn Half-Troll, for example; or Auðunn illskælda, ‘Auðunn the bad poet’ (I wonder if Wystan H, who famously ventured to Iceland, knew about Auðunn. If he did, I hope he was amused). The great tales also fix events historically, if unreliably, and paint a picture of a rough and rural society, albeit one with a sophisticated sense of itself. Njals saga—also known as brennu Njál, or ‘burnt Njal’ – ends with the siege of a farmstead that is finally burnt to the ground in scenes reminiscent of John Ford or Sam Peckinpah.

Njal is in fact Niall, being like so many Icelanders of Irish descent, and the sagas tell us much about relations between the two societies: prisoners, most of them women, were brought back from Viking raids to the island, and they imported their culture with them. In one of the best, Laxdæla saga, the slave Melkorka is believed to be a deaf-mute, until she reveals herself as an Irish princess, teaching her son Ólafr Irish Gaelic. Ólafr returns to Ireland and meets his grandfather, the Irish king Myrkjartan, who offers him his kingdom (Ólafr declines).

The stories are endlessly rich, with telling details—the beautiful girl in Njal’s saga who is thought to have brought ‘thief’s eyes’ into the house, for example—and revealing about a culture remote from our own and yet very recognisable. So those are what I’d like to curl up with (the Penguin translations by Magnus Magnusson, Robert Cooke and Keneva Kunz are outstanding) over the Yule season, ideally with a glass of crystal-clear Brennivín.

Oh and also a set of new clothes, please. Because you never know.

— Shaun Whiteside is a translator of French, Dutch, German, and Italian literature.

December 12

The book I want above all others for Christmas is The Satyricon, a Latin novel written in the first century AD by Petronius. Its anti-hero, Encolpius, is a temple robber and murderer. His adventures are by turn hair-raising and very funny.

All except one of the Greek novels surviving from antiquity are either set in the past or an alternative history. The Satyricon, however, is set in the contemporary Roman world. As such it gives an extraordinarily vivid insight into social and cultural history, into the way people thought.

Alas, only fragments survive of Petronius’ novel. (We know that the famous dinner-with-Trimalchio scene was in Book XV.)

As it is Christmas, I would like the whole novel, somehow miraculously rediscovered!

— Harry Sidebottom is an author and historian, whose latest book is The Shadow King.

December 11

Modern life is insane. Human beings have become human doings. We’re all at burnout and information overload—and this is before Technological Armageddon has really started (although it’s doing a fine job this year of expediting that process, which is kind of the point of its existence, but I digress…).

Merry Christmas to one and all, btw. My default, if all authors are to be replaced by AI and all other books burned by the machines soon to be taking over, is comedy. And specifically English comedy as a sub-category—the kind that self-deprecates, ridicules, finds the irony and humour in the most awful of situations.

So all I want for Christmas is a signed first edition hardback of A Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy by Douglas Adams. I go back to my crappy paperback copy whenever I’m down, whenever I’m happy, whenever I’m lost, whenever I’m exhausted. It never fails to make me laugh out loud. I had a chapter from it read out at my wedding (which, out of context, was a disaster—but I’m sure Douglas was laughing somewhere up in Space). Anyone who can write a whole chapter on warring worlds, the tragedy, the heartache of battle and then have it culminate with the aliens, upon arriving on Earth, being “swallowed by a small dog” due to a miscalculation of scale, wins my heart.

— Sophie Hilton is Creative Studio Director & Producer - Universal Music Recordings (Universal Music Group UK)

December 10

The book I would most want to be gifted in the whole world would be the original manuscript of the Book of Kells. The illuminated collection of folios of the Gospels is perhaps the most beautiful piece in the Western calligraphic tradition and arguably the finest piece of art to be produced in the British Isles. There are several reasons why I would like it, and specifically why I would be a good recipient of such a gift.

Firstly, as a clergyman, it should go without saying that I have a natural interest in religious books. Most of these, however, are quite boring and don’t have pictures. The ones that do tend to be a little simplistic, with lots of people wearing tea towels and wandering round Bible times. The vivid imaginings of Christ enthroned in glory would make a much appreciated change.

Secondly, I’m a pretty dab hand with a felt tip pen if I say so myself, and almost always keep inside the lines. So I’d be perfect to do the colouring in required to fill some of the gaps in the folios where the monks either got killed off by a Viking whilst working on the illumination or simply forgot to provide decoration. I’m less good with pencils as I find the essential chalkiness of the average lead to be unreliable and prone to snapping. However, I think felt tip would be the medium to best complement the existing 9th century yellow ochre and lapis lazuli pigments.

Thirdly, the book is currently displayed in Trinity College, Dublin where only two leaves of the book are ever on display at any one time, with the pages being turned every twelve weeks. Consequently, it would take nearly a lifetime to actually read the whole book. I, by contrast, would devour the whole thing on the afternoon of Christmas Day, probably while Doctor Who or Mrs Brown’s Boys or His Majesty the King or some other festive bumf is on the telly. I’d then read it again on Boxing Day and perhaps glance at it once or twice in early January alongside the Viz Annual or similar. This would still mean it had been read more than at any point since before the Norman Conquest.

Finally, when I did eventually get bored of it, I reckon it would fetch a pretty price on eBay, especially with all the extra colouring in. This might seem selfish, and doubtless some readers would suggest I should take it to Oxfam or, if they’re disqualified on human-trafficking-to-use-of-sex-slaves-in-Haiti grounds, the Cats Protection people. However, I think we can all agree that it would be a little ignominious for the masterpiece of Celtic Christian script to be reduced to 50p (or 3 for £1) alongside loads of Maeve Binchys and a signed copy of Glen Hoddle’s Playmaker: My Life and the Love of Football. Also, the eBay money could go in the piggy bank and help towards the purchase of the Codex Sinaiticus as a birthday present to myself next year.

— Fergus Butler-Gallie is a priest, and author of Touching Cloth.

December 9

My godson, Benjamin (7), asked his mother about ‘the new war’ he'd heard about at school. She started explaining but, a few sentences in, Benjamin interjected, "Okay, I know where you're going with this. Basically, it's another Smeds and Smoos."

As a child, I never read such books. When I came into English, a little late, I had to catch up with books like The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. So, it’s been a personal delight to read to Benjamin at bedtime, four or five times a week (he and his mom live just down the road). This way, I have discovered modern classics such as many of Julia Donaldson’s books—including The Smeds and The Smoos—or A.A.Milne’s, or Roald Dahl’s.

On Saturday mornings now, the mobile library comes to the village and Benjamin returns old books and takes out new ones, fiction and non-fiction, and when he comes home he buries himself in the sofa and reads for hours.

In a small, children’s bookshop last year, the owner approached him and asked what his favorite subject at school was. He replied “mathematics.” I didn’t know he had a favorite.

The bookseller looked surprised. “I’ve never heard anyone say that.”

“Well, now you have,” said Benjamin.

As it happens, Benjamin and I have a weekly Math Club, just the two of us, in which we discuss some mathematical idea. He then gives his mom and me a presentation of what he’s learned. Like many children, he’s a natural performer. He could, for instance, tell you about Hilbert’s Hotel—every room already taken—and how to accommodate new guests arriving in an infinite number of coaches, each carrying an infinite number of people.

So the book I’d really like to read to him this Christmas—one of five books, in fact, I would be pleased to write if a publisher will simply cover my costs—is one that would outline various mathematical concepts that don’t at first glance look like mathematics but nonetheless emphatically are. I imagine a lot of people would have the same reaction as Benjamin upon discovering these lovely things: a grin of deep gratification at recognising how damn cute they are.

Books bridge time and space. They make faraway things larger and ancient things present. Most of all, they engage the imagination because they cause us each to make impossible stuff real in our heads: whales that talk to snails, dragons, Smeds and Smoos, mathematically perfect circles and an infinity of hotel rooms…

You will have seen the recent headline that a million kids in Britain don’t own a single book. My heart breaks to imagine a child who isn’t read to, who does not get to discover the wondrous opportunities of the written word: its power to transport you, of course—but even more than that, to furnish you with things to think about, things that are fun to think about or things that are worth thinking about, and ways to ready you to think about this tragic and beautiful world around us.

— Zia Haider Rahman is the author of the novel In the Light of What We Know.

December 8

The book I would be happy to receive for Christmas, in pristine condition, is R.Frank Busby’s 1976 classic Manned Submersibles. With over 800 pages of diagrams and plans of every submersible ever made, Manned Submersibles is a treasure trove of arcane and specialised information about the niche world of… manned submersibles. These are those small sea craft that go deeper than mere submarines, which typically never venture below 3-400 metres, whereas a half decent submersible will be good to 3000 metres.

The world of submersibles, manned or otherwise, is a quiet and secretive one—until a disaster bursts upon the surface world, such as the recent Titan submersible, which suffered a coke-can collapse (technical term), while attempting to provide a tourist service for viewing the Titanic.

Alternatively, I suppose that I could settle for a complete One Thousand and One Nights, translated by Richard Francis Burton.

— Robert Twigger is the bestselling author of fifteen books translated into sixteen languages.

December 7

In 1885, in his house on the south coast of England, high on a fever and cocaine, Robert Louis Stevenson—thus far best known for Treasure Island, and still some distance from a famous author—scrawled down the original Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in just three days, declaring it the best and most important thing he’d ever written.

As always, Stevenson showed it first to his wife.

Intelligent, outspoken, strong willed and American-born… Fanny S hated it. In particular, she loathed that it was a story with no obvious, positive moral.

But what exactly happened next remains debatable.

The “accepted” version is that the bedbound, sickly Stevenson (think Elizabeth Barrett Browning with better hair) listened to reason, and when his wife came upstairs later, proudly pointed to a pile of ashes in the grate, inviting her approval. A variation on this sees RLS throwing his novella into the fire in a huff, and Fanny bravely trying to recover it from the flames.

The unsanitised version is that, fearing for her husband’s reputation if his story was published as written, Fanny herself torched the manuscript while Robert was still in the grip of fever.

‘I shall burn it after I show it to you,’ she had apparently written to a friend. And this is the version I believe, not least since Fanny is also on record as saying that, if she ever died, Robert’s devout and Calvinist father would need to approve her husband’s scripts in her place.

Which is not to say that she was wrong commercially.

Stevenson rewrote the book from scratch (again, in only three days, albeit with time spent later on revisions). Only this time he played up the morality angle, the conflict and contrast between the good, worthy and irredeemably bourgeois Dr Jekyll, and the brutish, wicked and proletarian Mr Hyde.

The Strange Case… was an immediate sensation with the Victorian reading classes, and Stevenson’s lasting literary fame assured. Sermons were preached praising his vision! The publisher sold 40,000 copies in the first six months. And for the first time in their married life Robert and Fanny weren’t in debt.

So all’s well that ends well—for Stevenson. But I‘d still like to wake up, Christmas morning, to a (Hyde-bound?) copy of that lost original. Preferably one wrapped in bloodstained brown paper, and crudely tied with butcher’s string.

— Jon Courtenay Grimwood is the author of twenty novels, most recently (as Jack Grimwood) Arctic Sun.

December 6

I would like to feel clever and claim a first edition Cien años de soledad—but it’s Christmas, a time for happy guiltless gluttony.

So instead, please, the complete works of Ina Garten, the Barefoot Contessa—with a fully-equipped kitchen, of course, and all the ingredients.

— Sonia Ruseler, former CNN anchor, is co-host of the Mujer Campante podcast.

December 5

How’s this for an All-Time Best Book Opening?

‘I, Hasan the son of Muhammad the weigh-master, I, Jean-Leon de Medici, circumcised at the hand of a barber and baptized at the hand of a pope, I am now called the African, but I am not from Africa, nor from Europe, nor from Arabia. I am also called the Granadan, the Fasi, the Zayyati, but I come from no country, from no city, no tribe. I am the son of the road, my country is the caravan, my life the most unexpected of voyages.’

Amin Maalouf’s masterpiece, Leo the African is the novelized story of the real-life Hassan al-Wazzan, a Muslim born in Granada around 1494.

Hustled out of Spain as Ferdinand and Isabella wrapped up the Reconquista, al-Wazzan joined his family in exile in Fes, the prelude to a wandering life throughout North Africa, and from Tikmbuktu to Constantinople. Captured by Barbary corsairs off Jerba c.1520, he was presented to Pope Leo X as a gift, an educated ornament for the papal court. Astutely converting to Christianity, ‘Leo Africanus’ was then renamed in honour of his patron, and freed from slavery—whereupon he devoted himself to his studies, publishing his evocative Description of Africa in 1526.

Part Ibn Battutah, part Forrest Gump, Maalouf’s Leo is witness to the fall of Granada and the Spanish Inquisition, the Ottoman conquest of Egypt, and Renaissance Rome under the Medicis. It is the Muslim world’s Candide, a picaresque, adventure-filled romp by an enlightened, multilingual man of many cultures.

In 1975, civil war broke out in Amin Maalouf’s native Lebanon, and he became an exile in Paris. Wise and humane, he wrote from bitter personal experience about war, ethnic tensions and the problems of cultural identity. In old age, Leo the African cautions his son: “Wherever you are, some will want to ask you questions about your skin or your prayers. Beware of gratifying their instincts, my son, beware of bending before the multitude! Muslim, Jew or Christian, they must take you as you are, or lose you. When men’s minds seem narrow to you, tell yourself that the land of God is broad; broad His hands and broad His heart. Never hesitate to go far away, beyond all seas, all frontiers, all countries, all beliefs.

Romanticised? Undoubtedly. Page-turning? I defy anyone not to storm through it in a spirit of delighted wonder. Claire Messud wrote that Maalouf’s work ‘recreates the thrill of childhood reading, that primitive mixture of learning about something unknown or unimagined and forgetting utterly about oneself.” I was perhaps eighteen when I met Leo the African. If I could have anything, this Christmas, it would be to wind back all those years, and discover his story once again, for the first time.

— Justin Marozzi, a historian and travel writer, is author of six books, including: The Man Who Invented History: Travels with Herodotus; Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood; and Islamic Empires - Fifteen Cities that Define a Civilization.

December 4

Top of my fantasy Christmas list—other than a winged horse—would be a first edition of US writer James Salter’s slim 1967 erotic masterpiece, A Sport and a Pastime. A quick browse of Google says this would set my beloved back at least $1000. So, dream on, Pelling.

The novel resembles The Great Gatsby in that the story is told by an American male (unnamed) who is peripheral to the action, but who is fixated on the gilded, careless protagonist. In this case Philip Dean, a college drop-out with a dazzling motor. The duo are spending time in post-war France but only the former has the means and moves to pick up a gorgeous young waitress, Anne-Marie, and seduce her.

The sex scenes are conveyed in shockingly intimate detail, which our narrator admits owe more to his imagination than actual knowledge of what’s occurred. The warning arrives early: “I am not telling the truth about Dean,” says our voyeur guide, “I am creating him out of my own inadequacies”.

Thanks, no doubt, to the lifting of the Lady Chatterley ban in 1960, Salter wasn’t censored for his audacious descriptions of oral and anal sex. Or perhaps it was simply the fact his writing about both France and sex is so lavishly sensual, so perfect, that petty criticism would be the real obscenity.

— Rowan Pelling is co-editor of Perspective magazine.

December 3

A deep sentimental attachment to my old English teacher Michael Meredith—who among many other things kindled in me a lifelong love of Browning (Robert, not gravy)—means that I'd love above all things a first edition of Pauline.

Michael solemnly charged all his pupils, as teenagers, with dedicating the rest of their lives to scouring the world's charity shops for one. Reason being 1) it was Browning's first publication, and his name isn't on it, so most people wouldn't recognise it for what it is; and 2) because of 1) you might make off with it for a fiver, and it's worth squillions.

If I got Pauline for Christmas I would 1) be rich and 2) feel able, without guilt, to spend less time in charity shops.

— Sam Leith is literary editor of The Spectator.

December 2

One book? Just one?? What damn fool editor came up with this idea…?!!

Alright, alright.

Living in a place with no bookshops, there is a lot of time to dream about the books I don’t have access to. Among the glorious dead, I’d love a first ed. Tristram Shandy. But I already have about ten copies of the book, in one edition or another, and a neighbour in the UK let me see his signed one, once—so this isn’t what you’d call strictly essential. A Johnson’s Dictionary would be fun, of course; but the well-stocked Stanley library has a full-size facsimile, if I really need to take a look at that. Seamus Heaney’s recent Letters (848pp!) turn out to have at least one splendidly rude poem in them; but I’ve still barely scratched the surface of last year’s equally hefty Translations. And only this morning I discovered the existence of an 1825 novel called Brother Jonathan: or, the New Englanders, which weighs in, across three volumes, at 1,324 pages of (among other things, presumably) ‘phonetic dialogue depicting drunken stuttering’… though one suspects that is not currently in print.

From the life-wrecking waves of new books published every sodding week, I was itching to read the rest of Jack Grimwood’s new Tom Fox thriller, Arctic Sun... and ‘Jack’ is such a bloody good egg that one is right now on its RAF-‘supported’ way to me. Andy Stanton’s Benny the Blue Whale (with a tiny penis) must win the prize for Least Expected Press Release of all time; but thankfully—wonderfully, hilariously—that has arrived here (finally). Shehan Karunatilaka’s The Birth Lottery and Other Surprises is certain to contain bedazzling gems; but so far it’s only available in India, and if I order it from there it will simply never turn up in the South Atlantic. You get the idea.

So the book that I would like this Christmas is Nick Cave’s unfilmed—and unfilmable—screenplay, Gladiator 2.

I’m a big fan of Cave’s work, both musically and on the page (and in the movies, come to that). But the story goes, here—so to speak—that Cave knew bloody well whatever he wrote was never going to see the light of day, so pushed the boat out further than Charon punting off across the Styx.

Maximus—still played by Russell Crowe—wakes up on the sand floor of the Colosseum, to find two thieves trying to strip him of his armour. Already dead, but not yet in Elysium, he soon discovers he is indeed echoing in eternity: in limbo, basically, and being shown round by a ghost called Mordecai.

In the chaos of the third century, the empire is collapsing, and the emperor Decius is blaming the Christians: ‘Rome weeps, and this little fish swims in her tears’ (#Christmas). Lucilla is dead, a martyred convert to the new religion, and her doe-eyed boy Lucius from the first film (whose skull Maximus could have crushed, etc.) has become an evil imperial enforcer, in the manner of his uncle Commodus. Juba the Numidian is still alive, and living in Rome. As is, er, Maximus’s son.

Result: equal parts Ben Hur, The Matrix and Apocalypse Now, tricked out with New Testament references, legit Latin poetry, and many a deft nod to Ridley Scott's now 23(!)-year-old original.

Yeah, the dates don’t add up, the names of gods flipflop between Roman and Greek, and Mordecai calls the local wine ‘rough as dog’s guts’ which is hard not to hear in an Australian accent. But there’s a naval battle in the Colosseum, a grinningly-facetious pastiche of the assassination of Julius Caesar, and a closing sequence that is, shall we say, unexpected.

Is it Nick Cave’s most profound work? No it isn’t. Does it piss me off the screenplay has never been published. Yes it does.

Gladiator was a big deal in my early adulthood. And now I’m old enough to know I probably don’t want to ruin it with any actual sequel (while also knowing that I’ll go and see it, anyway). This concern was amplified last week, when I found out that the script for the forthcoming Gladiator II was written by the man who did this year’s savagely-panned Napoleon.

But I’ve also recently discovered that a Falklands friend has taken up book-binding. So, since nobody will buy me books in any case—and lest someone someday switches off the internet—I’ve decided I’m gonna commission my own personal copy of Cave’s Gladiator 2, like some sort of insane horse-marrying emperor. I’m thinking purple binding, or perhaps black leather with ornate gold lettering. And to hell with the expense.

— ASH Smyth is co-editor of The Emigre.

December 1

All I want for Christmas is The Big Book of Breasts (Taschen, 2006). It’s not that I’m obsessed with breasts, big or otherwise, any more than the next person; it’s just that I’ve always fantasised about being interviewed live on a highbrow television culture show sitting in front of a towering bookcase that contains row upon row of wildly smutty titles. Sadly, for this lifelong dream of mine to materialise, TV cameras would have to be sent to my home, which probably means I’d need to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature, or something like that—but I’ve given this a lot of thought over the years, and I’m confident that would only make the gag work better.

The show’s producer would countdown in my earpiece, then I’d appear in real time on TV and computer screens across the world. I picture myself wearing a sweater vest, perched thoughtfully in a comfy old armchair in my oak-panelled study, adjacent to a roaring fire. I’d frown a lot, obviously, steeple my fingers under my chin, and maybe even puff on a pipe. It would all look perfectly proper and fitting for a man of my intellectual standing and global renown.

Only the discerning viewer would spot an impressive collection of Razzle annuals lining the shelves behind me, plus maybe fifty or so transexual pornographic DVDs, should those still exist, and, of course, The Big Book of Breasts.

In practice, the dream scenario would work just as well with The Bigger Book of Breasts (Taschen, 2023), The Big Book of Pussy (Taschen, 2011) or The Big Penis Book 3D (Taschen, 2008), or best yet the whole set—but the main point is the gruff presenter and I would discuss the future of literature as an art form and everything I’d say would be horribly dull and odiously predictable.

— Dominic Hilton is co-editor of The Emigre.