The Forgotten Irishman

by ASH Smyth

June 2023

Conor O Brien: apostrophe-hater, architect, mountaineer, boat-builder, writer, IRA gun-runner and officer of the Royal Navy.

This month, 100 years ago, Edward Conor Marshall O Brien (we shall return to the apostrophe) tacked out of Dun Laoghaire harbour in his brand new yacht, the Saoirse, with the intent to sail round the entire world.

And why not? He had, by this time, ticked off a lot of other things already.

Born in 1880, in a grand house in Co. Limerick, Conor O Brien grew up the grandson of William Smith O'Brien—Irish Member of Parliament and (apparently-reluctant) leader of the Young Ireland movement—in a comfortable environment of art, social reform, and upper-class Irish nationalism.

He got into both sailing and mountaineering as a boy, was sent to school at Winchester, and later graduated from Oxford as an architect. He went into professional practice in 1903, largely working on public-type buildings, of which only the Cope Hall and the People’s Hall in Limerick (the implied politics may or may not yet be relevant) are attributed to him. For a while, he also held the position of local Irish Agricultural Society architect for creameries.

It may be that O Brien simply didn’t spend much time at work. In 1913, for instance, he went on a casual mountaineering trip in Wales with a couple of minor players called George Mallory (also Winchester) and Geoffrey Winthrop Young (poet, journalist, conscientious objector, and author of The Roof-Climber's Guide to Trinity). He liked to do this sort of thing—as he did sailing—in bare feet. His grandniece said she once found OB and the future conqueror(?) of Everest hanging by their fingertips from the picture rails, just for funsies.

Related to various landed and noble families, O’Briens included, but openly ajudging himself to be somewhat apart from them, somewhere along the way he made the terribly modern decision to drop the apostrophe from his name.

A man otherwise fairly typical of his time and class, O Brien spoke fluent Irish, was an early member of Sinn Fein (as well as the United Arts Club), and was outspoken in the cause of Irish Home Rule—all of which fairly unusual for a Protestant.

By 1914 such politics had become ‘relevant’, and he joined the Irish Volunteers—a proto version of the IRA—using his own yacht, the Kelpie, to help Erskine Childers run guns into Ireland (from Germany) in the preludial months of WWI.

Man of adventure and ardent believer in nascent free state, he nonetheless soon lost sympathy for the more violent aspects of Irish republicanism. In an improbable volte-face, he promptly joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve!

Having survived the war unscathed, he was subsequently kept on by the Navy, on account of his distinguished service, and made commander of a fisheries-protection gunboat.

The Kelpie was lost in an accident off the (rocky) coast of Scotland, and in 1922 O Brien commissioned a new boat, a 20-tonne, 42ft ketch, from the boat-builders at the Baltimore Fishery School (no pun), in Kerry.

In 1923 he set out in the Saoirse—‘Freedom’, for non-Irish speakers; named for his newly liberated homeland—on a voyage round the world, which, if successful, would make him the first Irishman to circumnavigate the globe, the first person to do so from East to West, the first to sail via the three ‘great capes’ (Good Hope, Leeuwin, and Horn—a route til then reserved for considerably-larger grain clippers), and the first pleasure boat—and often vessel of any kind—to enter almost any of the ports along the way, flying the new flag of the state of Ireland.

Whether or not O Brien even consciously wanted to set these records is unclear. He seems, like so many adventurers before and since, primarily just to have relished the challenge, and even hardship.

The departure of this benchmark expedition was noticed in the leading Irish broadsheets of the day, and the Dublin intelligentsia allegedly placed bets as to the likelihood of the Saoirse’s crew being taken for pirates, under their 6-month-old tricolour, and finding themselves languishing in some Spanish jail.

In Funchal, in fact, some natives immediately mistook the flag to betoken their own unheralded independence. Politics was generally in the air: bumping into British soldiers and sailors, O Brien wondered if these very men might not be former adversaries… and decided to get back out on the open water.

Leaving Madeira, he and his two fellow sailors headed down the Atlantic, then from Pernambuco across to South Africa (immediately losing his crew, and trying unsuccessfully to sell the boat in Durban), and then to Melbourne, where, even if another crew change had not proved necessary, he put in because he was ‘almost out of potatoes’. Irish jokes notwithstanding, O Brien had something of a fixation with regard to potatoes, writing that ‘potatoes are the seaman’s greatest curse. There are only three places in the world where they are worth taking on board. Ireland, Tristan da Cunha, and Argentina.’

He arrived in New Zealand too late to do a spot of climbing on Mt Cook, which may—it has been suggested—actually have been the point of the entire voyage in the first place.

‘Mr. O Brien's plain seamanlike account,’ wrote master yachtsman Claud Worth later, in the original introduction to Across Three Oceans: a Voyage in the Yacht Saoirse, ‘is so modestly written that a casual reader might miss its full significance. But anyone who knows anything of the sea, following the course of the vessel day by day on the chart, will realize the good seamanship, vigilance and endurance required to drive this little bluff-bowed vessel, with her foul uncoppered bottom, at speeds of 150 to 170 miles a day, as well as the weight of wind and sea which must sometimes have been encountered.’

But O Brien ploughed on, through all manner of trials and tribulations (incl. financial ones—at one stage being bailed out by his artist brother!), with a stereotypically-stoical good humour.*

Or at least that is how he comes across in his own book. The publicity around the Saoirse’s departure made specific reference to the galley apparatus, and O Brien’s alleged dictum that ‘the most important thing in cruising in a small boat is to feed the men well.’ Alas, however well fed his crew-members may have been, O Brien’s companions/employees were also always fed up, hence the continual desertions. Like many a driven human being, he was perhaps not the easiest man with whom to spend long spells in testing circumstances.

Still, in early December 1924, forty-six days after leaving Auckland, the Saoirse and her crew appeared within sight of the Falkland Islands.

Like rather a lot of sailors in the course of history, O Brien does not appear to have had had any intention of visiting the Falklands. And indeed he almost didn’t.

Swept along by eastward currents, ‘by the time I had got clear of Staten Island [the Argentinean one] I thought it would be a hopelessly long job to try to get to Montevideo, especially as the potatoes [see?] and flour were running low… So considering that after all Montevideo was very much like any other small country, I made an amusement of a necessity and carried on to the north-eastward.’

His watchkeeper then seemingly fell asleep at the wheel during the night, and they only just happened upon Beauchene Island, some 40 miles further south than any other of the 780-odd Falkland Islands. He remarks on the uselessly-flat Lafonia landmass, from the point of view of navigation, and the ‘smart breeze of wind blowing, as is almost invariably the case here during the daytime.’ Ain’t that the truth.

The Saoirse struggled somewhat coming West into Port William, and looked with a mixture of relief and scepticism at the steam-launch that came out to tow them in, from Stanley (‘that launch was rather notorious in the matter of salvage claims’). But, O Brien wrote, ‘I need hardly add I was charged nothing for the tow, for this was a different sort of colony that I had come to…’ With Christmas fast approaching, ‘I was overwhelmed with hospitality.’

His immediate conclusions on the Islands were, as is quite often the case, frankly, not totally flattering. With typical directness, the Falklands chapter of Across Three Oceans opens:

‘I suppose the Governor saw me looking with a critical eye on the amenities of Stanley – of which there are none – for he commanded the Seal Protection Cruiser to take me round the coast and demonstrate that not all his domain was desert…’

‘There is no soil,’ our wide-eyed traveller goes on (still in the first paragraph), ‘no warmth in the sun, no trees will grow, and only the hardiest weeds.’ This is mid-summer, I just remind the reader.

Horticulture is ‘a farce’, O Brien says, observing ‘a desolation’ of ‘stones and wind’, where gulls drop bones on the inhabitants’ greenhouses hard enough to crack the glass. ‘The scenery of East Falkland is not impressive… As wintry-looking a landscape as I ever saw… hardly a touch of green anywhere.’

‘The people live pecuniarily on wool, and gastronomically on mutton.’ Though at least, he discovers, ‘a few enthusiasts have constructed gardens in the lee of a stout fence and are even reported to have raised potatoes therein.’ Gods be praised.

The weather was then as it is now—‘the only difference between summer and winter is in the length of the days’ —but O Brien soon warmed (lit.) to the place enough to stick around for a couple of months. He was especially taken with the penguins, whom he travelled far and wide to see in major rookeries in places like the Jason Islands. A man apparently equally at home in dangerous waters and at dangerous heights is endearingly mystified as to why rockhopper penguins choose to nest on clifftops, the logistics of their feeding habits, and how they avoid in turn feeding the seals and killer whales that fill the waters. ‘Is anything more incredible than a penguin?’ He is dreadfully embarrassed when, on one occasion, he nearly steps (barefoot, of course) right through a jackass burrow.

‘The geese, after the wind, are the second curse of the country… All one can say about them is that they are easy to shoot and good to eat.’ (Can confirm, on both counts.)

And as for the seals, he narrates the disagreement between authorities of the time as to whether the pups are made to swallow stones as ballast, or to ‘to knock off intestinal worms’. In this mildly Herodotean section, ‘I had’, he confesses, ‘very vague ideas’ about these animals (although both of us now know that a large drifter could steam seven miles on the oil from one sealion).

In terms of the human population, O Brien was particularly happy to find himself being ferried about by other people for a change, especially when it comes to some ‘exciting’ passages between the northernmost islands. ‘One must have been a ship’s captain’, he wrote, ‘to appreciate being a passenger.’

Discovering a general preference for both landscape and climate as he headed West, they anchored outside settlements each night, as was the custom. ‘In a country with only 2,000 inhabitants all told everybody knows everybody else.’

He, too, seems to have been well-liked by the Islanders. He goes to San Carlos, ostensibly to get the Saoirse’s hull scrubbed (but mainly just to avoid putting back to sea), and, according to the Falkland Islands Magazine and Church Paper, the children of San Carlos were vastly amused to see a grown-up wearing shorts. The adults were pleased to see him because he’d been talked into bringing out their mail. He ends up bouncing up and down the coastline of East Falkland, and experiencing a somewhat ‘breathless performance’ navigating—with advice from a local pilot—the nooks and crannies of the Darwin area.

Even the government thought highly enough of O Brien to send him to Antarctica (the British chunk of which was then governed directly from Stanley) to report on the state of the whaling industry there. ‘Apart from whales,’ he reported back, ‘the South Shetland Islands have no excuse for existing.’ Before he finally departed on the last leg of his epic journey, yet another of his crew maintained tradition by jumping ship, to get married and settle down in Stanley.

Conor O Brien returned home in June 1925, two years to the day since he had set out, to a crowd of 10,000 and a hero’s welcome. The Irish Times wrote of him as ‘an ambassador, carrying the flag to places where it was unknown.’

Later that year, O Brien decided he should enter politics. He campaigned for a seat in the Irish parliament, as a member of Sinn Fein, the venture ending predictably when party administrators asked him for a publicity photo, and he gave them a picture of himself in Royal Navy uniform.

But if Irish government had no use for him, the Falklands still did. The sturdiness of the Saoirse had impressed everybody in their choppy waters—so much so that in 1926 O Brien was asked to design another boat (also built by the Baltimore school), for service in the South Atlantic.

The following year, he delivered the Ilen (named for a West Cork river) himself, with assistance from the Cadogan brothers: ‘the most enjoyable of all my voyages.’ This time, no-one deserted; and the Ilen remained in service for some seven decades, a further testament to O Brien’s capabilities.

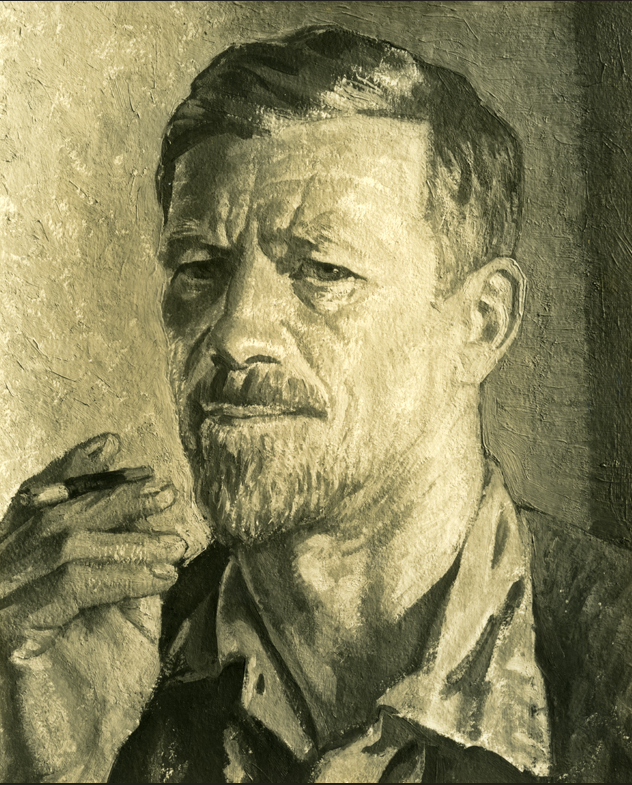

In 1928, the ruggedly handsome 48-year-old mariner married an artist, Katherine Clausen. They went to live in Ibiza, cruised around the Mediterranean in the Saoirse, and worked together on several literary projects as his ‘career’ careered around another bend.

In all, O Brien published 14 books: eight volumes about yachting, largely technical in nature, including From three yachts: Kelpie, Saoirse and Ilen (also subtitled A Cruiser’s Outlook. Unhelpfully, NB, almost any conversation about O Brien will begin with a couple of minutes’ disentanglement from the assumption that you want to talk about Conor Cruise O’Brien, the rather better-known Irish diplomat and, yes, writer); and half a dozen children’s books, full of good clean fun, self-sufficiency and outdoorsy virtue, with ripping titles like The Castaways, Atlantic Adventure, and The Luck of the Golden Salmon. These are, alas, now quite hard to get hold of.

Tragically, Kitty died young, in 1936, and O Brien sold the Saoirse, and withdrew into semi-reclusion on an island in the Shannon. Too old for active service when WWII broke out, he came out of retirement to captain vessels across the Atlantic for the Small Vessels Pool, and then returned to Foynes Island. From time to time, he would put all his clothes on top of his head, and swim across to the pub on the mainland.

He died in 1952, and was buried in the grounds of a ruined church beside the river.

And yet, for all that extraordinary, romantic stuff (Dominic West to star), O Brien is now almost entirely forgotten. I certainly had never heard of him, til Professor Jim McAdam (editor of the Falkland Islands Journal) gave a lecture on him, several months ago, at the museum in Stanley.

Ireland’s greatest yachtsman was barely accorded a decent obituary in any of the Irish papers (a half-paragraph in the Limerick Leader was the extent of it), he is commemorated in only a couple of remote or specialist places, and only a few years back was the first biography produced, Judith Hill’s In Search of Islands, the author herself describing it as ‘A first attempt to… portray something of his extraordinary spirit.’

This may well be, Prof. McAdam suggests, because O Brien—‘a man who sought action on his own terms’—just did not fit neatly enough into any boxes. At any rate, this spectacularly accomplished man has, in McAdam’s words, ‘largely been lost from Irish history.’

There is, sadly, nothing of O Brien’s in the Stanley museum, either.

Or perhaps I should say ‘not any more’. And/Or ‘not directly’…

In 1925, while waiting for his Antarctic excursion, Conor O Brien had had the Saoirse refitted at the government dockyard in Stanley. While there, he spent some time repairing ‘a little bit of carved and gilt gingerbread work’ damaged in Durban: namely, the insignia of the Royal Irish Yacht Club, where the boat was registered. ‘The Colonial Secretary, seeing me at this work, bade me design a Coat of Arms for the Colony (for he had fallen foul of the College of Heralds), and I… without regard to what was thought of my trick in Queen Victoria Street, had to comply.’

The resulting emblem—a shield with John Davis’s ship Desire and a seal on it—became part of the official flag of the Falkland Islands that same year. And it remains the cap-badge of the Falkland Islands Defence Force. When the flag was changed in 1948, a sheep being substituted for the seal, there was apparently almost a mutiny within the FIDF at the connotations of such an animal upon their uniforms. The Force stuck to their guns (as it were), and almost a century after its creation, O Brien’s seal seal could be seen worn with pride by representatives of the Defence Force at the King of England’s coronation—a curious trajectory for something drawn up by a former member of the IRA.

--

*‘Such is fame’, he shrugs, on history’s having forgotten everything about Captain van Hoorn, discoverer of the so-called Cape—‘not a Cape, but an island’—at the tip of South America. The better reason for this, though, may be that Capt v Hoorn did not in fact exist. The kaap was named by Dutch seafarers for the town of Hoorn.