The Guitarists’ Guitarists’ Guitarist

By Richard Simon

January 2023

Rock ’n’ roll and its multitudinous subgenres never caught on in the backward, impoverished ethnocracy where I grew up. There was just one state-owned radio station, whose English-language ‘commercial’ channel sounded like the BBC’s Light Programme c. 1950, but with adverts; as for television, it simply didn’t exist. Records and the equipment to play them were among the many foreign ‘luxuries’ that were subject to punitive import duties or banned altogether. Western ‘immorality’ was deplored by the local cultural authorities. Censorship was rife.

For all that, I and some of my contemporaries still managed to develop rock-’n’-roll hearts and even form a tiny underground musical community (coterie would be more accurate) within the notionally privileged Anglophone minority to which we belonged. A few of us really were rich and could afford to import or smuggle in LPs, which were then bootlegged on cassette and passed around by the rest of us, who were mostly broke. Now and then a film like Woodstock or The Concert for Bangladesh would slip in under the oppressive nativist radar and land in a local cinema, giving us a glimpse of our heroes in action. A few of us were inspired by these epiphanies to form bands ourselves.

Given all this, it is hardly surprising that I barely heard a note recorded by Jeff Beck until I was about twenty. I had heard plenty from Hendrix and Clapton and Jimmy Page, with whom he was often mentioned in the same breath, but he, not having enjoyed the same commercial success as these other virtuosi, never fully made it out, so to speak, to the colonies. It was only when I was sent off to study in England, where my musical education really took off (my academic education, sad to say, did not), that I discovered him. I was rummaging through the campus radio-station library, looking for songs to play on the little-listened-to redeye slot I’d been assigned as a tyro DJ, when I came across a copy of Blow by Blow.

I don’t remember, now, why I put Side Two on first.

The sound that flowed out of the cans was like nothing I’d ever heard before. Thick and creamy, calorific but not especially sweet, it provoked immediate synaesthesia: it felt chewy in the mouth. It didn’t really sound electric; it had more in common with a ’cello or viola than with any amplified plank. There wasn’t even any twang in the opening section, because Beck was using the volume control on the instrument to produce a ‘bowed’ effect. But no ’cello was ever so round, so full, so richly endowed with plangent harmonics as this. Hearing it in that moment, I thought it was the most beautiful sound in the world.

The track was, of course, ‘Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers’, Stevie Wonder’s apologetic gift to Jeff after Berry Gordy clawed back the commercial rights to ‘Superstition’, which Wonder had co-written with Beck in 1972. It is still my favourite Jeff Beck track, especially in the live version from his career-defining 2007 gig at Ronnie Scott’s. By then, that tone had become his “signature sound”, but the fact is that, even on that song – probably the first time he ever got that tone down, fully realised, on tape – it was only one of many timbres Beck employed. By the middle of the first chorus he already sounds different, and his tone changes many more times through the track – most frequently in the solo section – before returning, in the dying moments, to the sound he began with. This, in fact, is Jeff Beck’s real ‘signature tone’ – not a single sound but an endless procession of timbral changes, not just from song to song, part to part or section to section, but within the same measure, the same phrase, often the same note.

“The sound that flowed out of the cans was like nothing I’d ever heard before. I thought it was the most beautiful sound in the world.”

Some of this, of course, was achieved with electronic effects. Beck didn’t invent the intentional use of amplifier feedback but he was the first to learn how to control its pitch; he was an early adopter of the wah-wah pedal and one of the first guitarists to employ the orally-controlled modulation device known as the talk-box, later made famous by Peter Frampton and Joe Walsh. Beck’s version was a bag, not a box, but the principle was the same. Yet these gadgets, which any guitarist can buy and learn to use, were mere garnish to him. Clapton, ever envious of his less-successful contemporary but scrupulously truthful as he always is, nailed it. “With Jeff,” he said, “it’s all in the hands.”

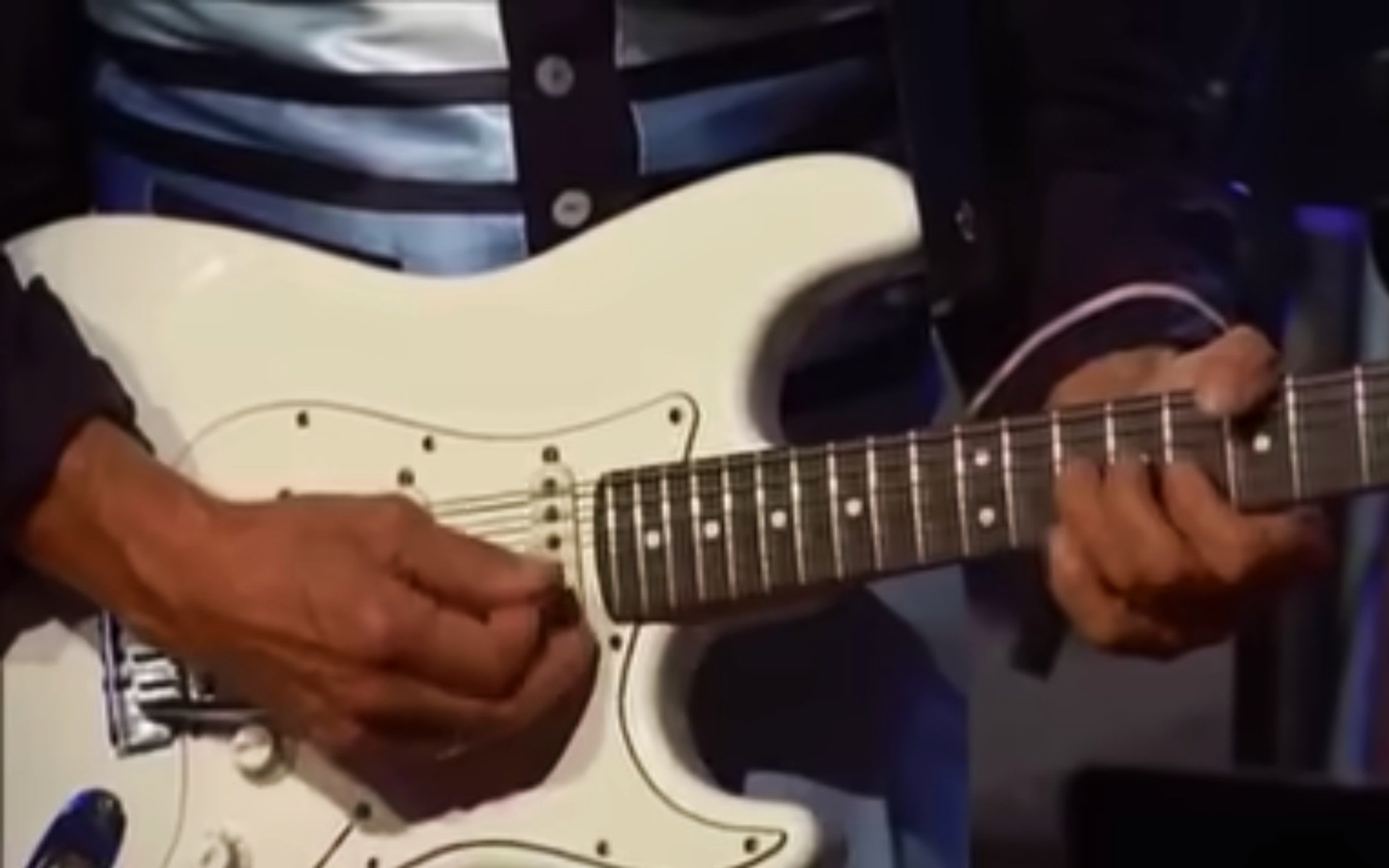

And man, were those hands busy. Besides the use of various accessories, guitarists achieve timbral changes by varying their manual impact on the strings and body of the instrument. This was the true locus of Jeff Beck’s genius. As you may have guessed already, I too, am a guitarist, and I have watched him play on video – scrutinized him would be more accurate – times without number. Unlike Hendrix, whose fingers always seem to be doing something different from what you hear coming out of the speakers, Beck’s technique is visually transparent: you can see exactly what he’s doing and how he’s doing it. Well, I can, anyway – not that it does me any good, because I can’t do it. It’s too precise, too fast, too fiddly, too bloody hard. I mean, even God gave up trying, so what do you expect from a mere mortal?

The guitar he used to record ‘Cause We’ve Ended…’ was a one-off, a hybrid axe built by the luthier Seymour Duncan, but it wasn’t the instrument he was fondest of. That was his famous white Fender Stratocaster, whose action was set up like a hair-trigger: the balance springs under the bridge loosened to make the vibrato arm as sensitive (i.e. floppy) as possible, the bridge itself raised high to allow extreme bends, often as much as a fifth above the fretted note, the volume and tone controls lubricated until he could turn them with the lightest touch of his little finger. Playing that guitar must have been like walking a well-greased tightrope, yet despite the built-in potential for disaster, Beck, as the guitar teacher and record producer Rick Beato affirms, “never played a bad note”. Actually, that’s a bit of an exaggeration – he played some pretty awful ones with the Yardbirds, the Tridents and even with the Jeff Beck Group (‘Old Man River’, anyone?) – but it’s certainly true of his mature phase, which began with Blow by Blow under the avuncular aegis of George Martin and lasted all the way into last week.

I could go on for pages about his technique, but this is a family magazine, not Guitar Fetish Weekly, so I’ll put a sock in it. Still, I’m delighted that someone gave me the opportunity to write about Beck for public consumption. Apart from a well-documented impatience and sharpness of temper – traits his handsomely wolfish face frankly advertised – he was an altogether admirable figure, an artist who insisted on placing quality of work and life before wealth and career and still managed to achieve vast recognition, most notably from his closest competitors, and contrived to amass a fortune that was recently assessed at $18m. With gallant insouciance, he built and raced cars with his own irreplaceable hands (which were, in fact, insured for $10m). Otherwise, he contrived to avoid the well-known pitfalls of a rock-’n’-roll or show business career, retaining both his health and his integrity until the end, and kept his private life private. He enjoyed a joke; his one grouse against Clapton was that God lacked any perceptible trace of a sense of humour. As a guitarist, he was always trying to improve.

“Instead of mourning his passing, we should be holding funeral games for him, as they did for Achilles.”

I only ever saw him live once, at Guildford Civic Hall on 18 May 1980. Sadly, it wasn’t one of his own gigs but an Eric Clapton concert. Eric, who was then well into what Albert Lee – who was also on stage that night – called his brandy-for-breakfast years, was fronting a formidable band: Chas Hodges on piano, Gary Brooker on organ, two of the MGs (I think) for the rhythm section and Lee as second guitarist. Beck slouched on unannounced towards the end, cradling his white Strat, but he wasn’t turned up loud enough to cut through the mix and you could see he wasn’t really trying, anyway. When the band came back for the encore, he whipped out a couple of spray cans and spurted arcs of iridescent pink and gold goo over the others till they looked like blobby, spangled stalagmites. Then Chas (I think it was) got hold of one of the cans and did the same to him, and that was how the show ended. He didn’t add much to the music that night, but he certainly made his mark.

The day he died, my email and social media were clogged with messages of sympathy from friends who knew how much he meant to me. I couldn’t be sorry myself, though: not at all. As I have said elsewhere, his was a heroic and exemplary life. Instead of mourning his passing, we should be holding funeral games for him, as they did for Achilles. Or, at the very least, name a star after him.