Where Was I?

by Martin Rowson

December 2024

Martin Rowson on the original unfilmable (and indeed unreadable) ‘anti-novel’, Tristram Shandy.

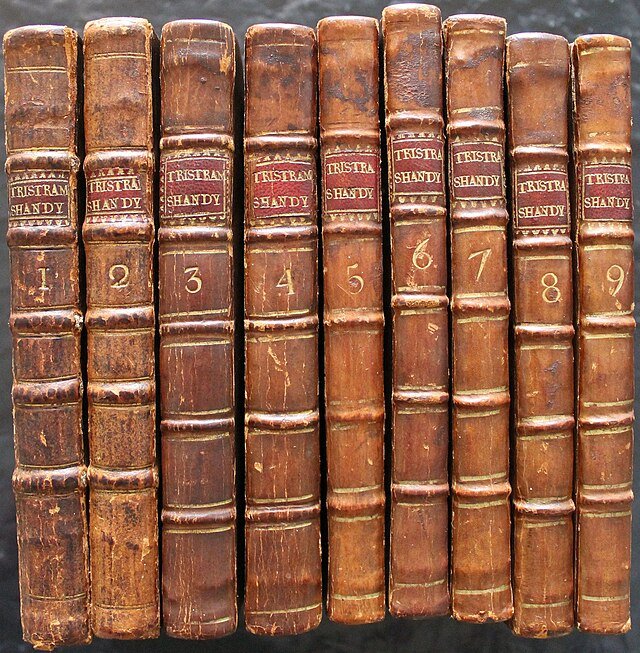

Michael Winterbottom’s A Cock and Bull Story purports to be a film of Laurence Sterne’s ‘unfilmable’ novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, published in nine volumes between 1759 and 1767. Indeed, the publicity material makes a great deal of the book’s ‘unfilmability’, and the finished product lives up to all that Winterbottom, the audience or even Rev Sterne could wish for. Which is not a criticism, but instead the humblest of admiring genuflections to a film about making a film about a book about writing a book. But forgive me. We’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The more enduring problem for Tristram Shandy has been not so much its unfilmability as its unreadability. In this regard, it fulfils all the criteria for a classic of English literature: most people of taste and a vague pretension to learning will, of course, have heard of it; will have every intention one day of reading it, save for the interruptions of daily life conspiring against this happy eventuality; will even have a shrewdish idea what the book is about (or not about); but will admit, under gentle pressure, to be waiting for the Andrew Davies TV adaptation.

That said, few people have actually read it. Among the great majority (and I don’t mean the dead—I’ll get on to them later) are Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon, the stars of A Cock and Bull Story, who admitted on The Jonathan Ross Show on BBC One that they hadn’t read the book. Brydon went further in a recent interview and said he’d gone into Waterstone’s, taken one look at the book and run a mile. These confessions were made while both men were on the circuit to publicize the film of the unfilmable book they haven’t read. In the film itself, there’s a scene where the Steve Coogan character—being either himself or being played as a character called Steve Coogan—tries to read the book but instead falls asleep and has a nightmare about making the film— of the book—in a film about making the film about the book.

Tristram Shandy is, without question, very, very odd. Its unreadability cannot, therefore, be put down simply to 250 years’ worth of accretion of layers of obscurity, and I reckon more living people have read it than have read, say, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela. But even 250 years ago it was seen as ‘difficult’. Dr Johnson himself remarked: ‘Nothing odd will do long. Tristram Shandy did not last.’ (To digress for a moment, it could be that Johnson was motivated by personal malice. Sterne was, then, much more famous than Johnson, and that would have annoyed him quite enough when the two men met. Worse still, Johnson claimed to have been deeply shocked when the Yorkshire parson showed him a pornographic drawing.)

“The more enduring problem for Tristram Shandy has been not so much its unfilmability as its unreadability.”

Forgive me again, and let’s go back a paragraph and a half. I was imprecise. Few living people have read Tristram Shandy, which is not to say that dead people now read it (although it is a movingly Shandean thought that heaven is filled with souls reading little else) but that in the mid-eighteenth century, Dr Johnson notwithstanding, the book was a runaway bestseller. More than that, it was a publishing phenomenon that turned Sterne from an obscure provincial clergyman into one of the greatest celebrities of Georgian London. So great was his fame that, when his corpse was disinterred by resurrection men for dissection at the schools of anatomy, he was recognized on the slab and speedily reinterred. Moreover, Johnson was doubly wrong. ‘Tristram Shandy did not last’ concedes a flash-in-the-pan celebrity for the book, but with that ‘did’ passes an inexorable judgement that the novel had already slipped through the fingers of posterity. Yet Tristram Shandy has never been out of print, and to this day has a dedicated, almost fanatical band of followers.

What gets these people so excited will have to wait. This is, after all, an article about a film about a book which is about the impossibility of writing a book. To aid comprehension and help you keep your temper, I should step back for the briefest of moments and inform you that, in 1996, Picador published my comic-book version of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, a volume now sadly out of print, but which was saved from pulping because every last copy sold. In the thin amount of research I did for the book, I met a good number of these devoted Shandeans. One such was Sir Stephen Tumim, Her Majesty’s late Chief Inspector of Prisons, who said that his greatest achievement was to end ‘slopping out’. When he was on Desert Island Discs, his book choice was, inevitably, Tristram Shandy, while his luxury was Nollekens’ bust of Laurence Sterne.

Before I met Tumim, I’d travelled to Coxwold in North Yorkshire to visit Shandy Hall, the medieval house Sterne bought with the money he made from Tristram Shandy. This building had been rescued from ruination many decades before by Kenneth Monkman, founder of the Laurence Sterne Trust, to whom I showed the first few pages of my comic-book interpretation of a novel that had been written, to a large extent, in his home.

To begin with, Monkman was highly suspicious of me. Shandeans, like any other group of fans, are jealously protective of the object of their veneration. (Some months previously, I’d told the journalist Francis Wheen I was planning to give Tristram Shandy graphic life; he’d glowered at me menacingly and growled ‘Watch it!’) So, as Monkman showed me round his house, I knew I had to win his trust. I did this in what I hope was a suitably Shandean manner, by repeating to him the story of Sterne’s father, an ensign in the army stationed in Ireland, who had a duel over the ownership of a duck.

The duel was held indoors, and Ensign Sterne was impaled through the shoulder, his opponent’s blade pinning him to the wall. With foresight, Sterne père told the victor he’d be obliged if he were to wipe the blade clean of lathe and plaster before withdrawing it through his body. Thus did Sterne’s father avoid septicaemia.

I, having presented my credentials as one of the cognoscenti, was thereafter treated with considerably more trust. Monkman showed me Nollekens’ bust of Sterne, told me that reading Tristram Shandy as a young man had changed his life and, best of all, when my book was published, he gave it his blessing.

“Tristram Shandy is, without question, very, very odd.”

Thanks to my comic book I have, I suppose, become a kind of honorary Shandean. Learned academics, many of a type satirized by Sterne in Tristram Shandy, have given lectures on my version. I’ve appeared several times in The Shandean, an annual compendium of Shandean studies, within the pages of which I was also once sternly upbraided by Prof. Melvyn New, who has devoted his life to the study of Tristram Shandy within the cloisters of the University of Florida. My crime was that I had shown insufficient reverence for the text.

Cutting to the chase, the text is really the major problem with Tristram Shandy. Most of the people who know about the book but haven’t read it know that Sterne plays all sorts of games with the text, layout, punctuation and everything else. This is why Tristram Shandy is often called, fliply, the first postmodern novel. Previously, it has been called the precursor to stream-of-consciousness mode, surreal, odd (of course), unreadable (naturally), as well as being recognized since its first publication as utterly filthy: in the opening chapter, the eponymous narrator describes his conception, and how it was interrupted through the operation of John Locke’s theory on the association of ideas when Tristram’s mother, associating Walter Shandy’s winding of the clock on the first Sunday of every month with the monthly discharge of his conjugal duties, says, mid-coitus: Pray, my Dear, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?

Tristram accounts all his subsequent misfortunes, including his misnaming, the flattening of his nose and his circumcision by a falling sash window, to this instigating error—And after the first two volumes of Tristram Shandy were published, the clockmakers of Clerkenwell addressed a public letter to Mr Tristram Shandy calling on him to retract his comments and disassociate them from such smut.

Where was I? Ah yes. Now, everyone who’s never read it knows that Tristram Shandy is littered with marbled pages—black pages—blank pages—pages of punctuation—dedications that suddenly pop up in the middle of a volume—diagrams of how the plot has got lost and how the digressions have looped and thrashed about and knotted themselves round the linear flow of the narrative—in addition to a narrative style which never, ever seems to get to the point. Famously, Tristram doesn’t manage to get round to his own birth until Volume 3. He concludes that the only way he can get his father and his Uncle Toby (whose wound on the groin received at the Siege of Namur provides a parallel subplot that leads up to a cheap sight gag, truncated and rather ruined in A Cock and Bull Story) down the stairs is to call for a ‘day-tall critic’ to erect some curtains at the foot of the staircase—and reflects at length that, at the pace he’s proceeding, his life will not be long enough to record all the events in it.

(To digress, by your leave, for yet another brief instant, there is a story by Jorge Luis Borges, the title of which would only delay us further, in which a cartographer makes a map of a country so detailed that he is forced to produce it in a scale of 1:1, the map covering the entire land area of the country mapped. If I’ve tried your patience too greatly, you may at this stage safely read no further.)

“I failed to read Tristram Shandy for a second time when I was at Cambridge.”

None of which, to return, makes Tristram Shandy an easy read, although it must be said it also encourages in the reader in no way whatsoever a desire to show any more reverence for the text than Sterne himself does. It was with this partly in mind that I failed to read Tristram Shandy for a second time when I was at Cambridge, scampering through the canon of Eng lit when we stopped—briefly—at Tristram Shandy. My supervisor for the eighteenth-century paper was a particularly calcified old fossil who never allowed his students to write more than two sides of foolscap and would spend most of the supervision fixing the seat of his chair and not listening to a word you were saying. In this spirit, I said that Tristram Shandy was a book that could be read backwards with as much profit as reading it forwards, and that ‘Lillibullero’, which Uncle Toby whistles in response to any discussion he finds embarrassing or stupid, is also the call sign of the BBC World Service.

(This, incidentally, is a fine example of the Shandean school of criticism Sterne hints at and I expanded on in our respective versions of Tristram Shandy.) The don responded thus: Just as Waiting for Godot would have been impossible without a tradition of more conventional theatre, so it is with Tristram Shandy, which should be seen purely as a cul-de-sac in the Development of the Novel. (This was more than 25 years ago—they were still very big on the Development of the Novel back then.) In a way, he was right. Tristram Shandy is an anti-novel (and think more anti-matter than anti-Pope); more than that, it is a direct satire on the whole idea of The Novel as It Was Then Developing, which was as an entirely selective and therefore ultimately mendacious attempt to simulate reality. Tristram Shandy, contrariwise, gives you the lot: and the best joke in the whole of this odd, rude, sentimental and, ultimately, profoundly disrespectful text is the impossibility of doing just that.

In short (please), Tristram Shandy is both unfilmable and unreadable because it’s about life in all its ludicrous detail: once you start reading it you’re compelled, like Tumim and Monkman (and like Tristram), to live it. To his credit, Winterbottom doesn’t even try, but skips and curvets his way through a wonderfully funny film about the impossibility of making a film about a book about the impossibility of writing a book. Furthermore, to return [next 40,000 words cut for reasons of space]

This article was first published in The Telegraph, in January 2006. It now forms part of As I Please: And Other Writings, 1986–2024, published by Seagull Books.