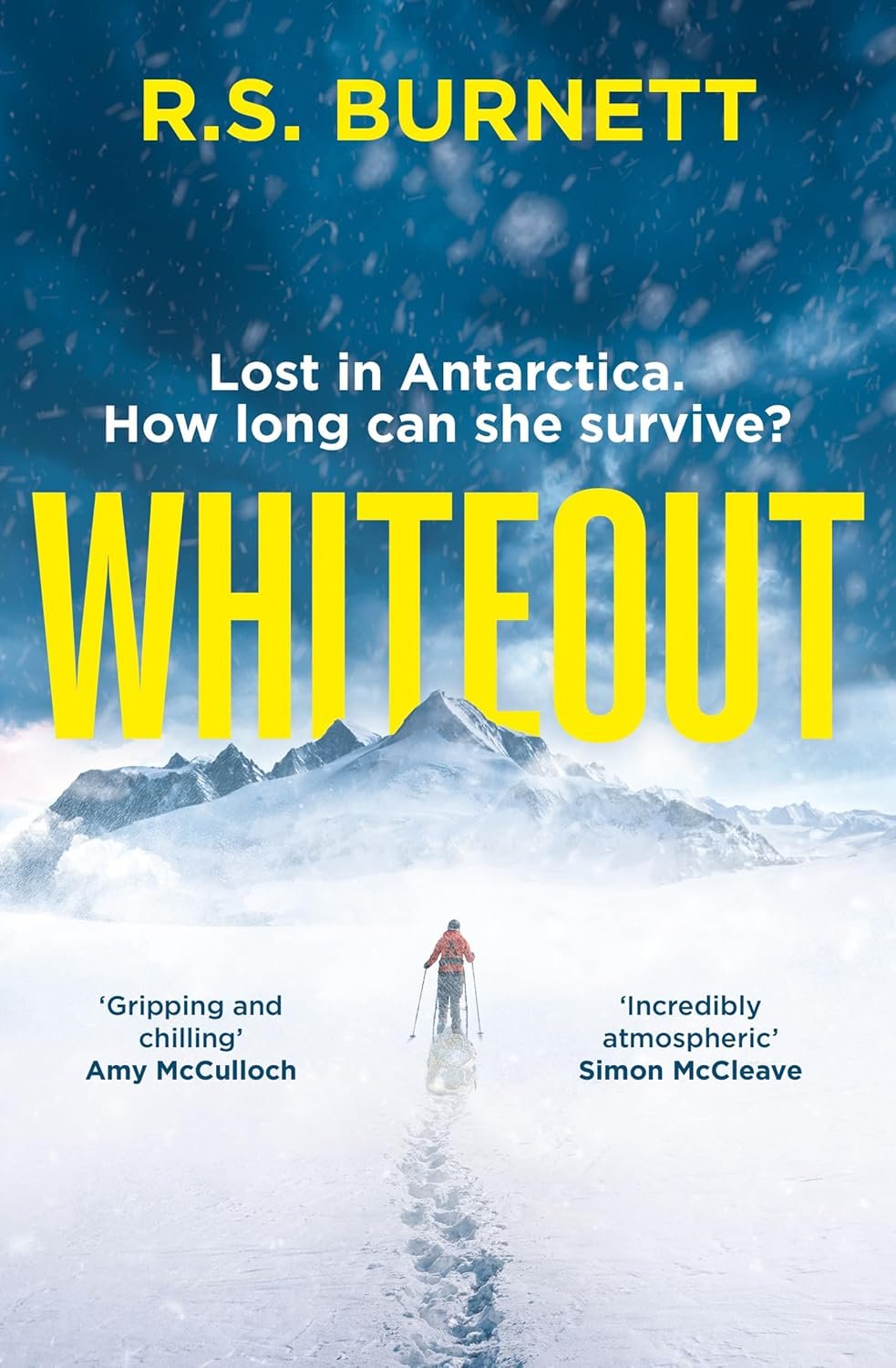

Total Whiteout

by RS Burnett & ASH Smyth

February 2025

ASH Smyth talks to RS Burnett about his Antarctic thriller debut, and the long road to publication.

ASH Smyth: The temperature is -69°C, life expectancy is 14 days, and the outlook is bleak—as well one might imagine. Rob, give us a run-down of what’s going here. Without spoilers!

RS Burnett: So, our story opens in a remote research out-station in deepest Antarctica, well inland, in the middle of the polar winter. So we have round-the-clock darkness, the temperature is very, very low, and our protagonist, Rachel, is in this very lonely outpost, on her own, and in these very cold, dark, harsh conditions not only is she on her own, she has been cut off: she’s lost contact with the rest of her expedition. For about a month she’s heard nothing from her colleagues, she’s running out of supplies, she has no means of leaving, and the only info she’s been getting from the outside world is a looped emergency radio broadcast from the BBC, informing her that the UK has been attacked with nuclear weapons.

ASHS: Alright. Now, I have to say, there's a heroic sort of stay-at-home-dad figure who happens to be called Adam, and I very much vibed with that.

RSB: Ha! Yeah…

ASHS: I also enjoyed all the musical references. Talk to me about the implicit—sometimes explicit—Pink Floyd soundtrack throughout the book. As far as I make out, they’re the only band mentioned. Are they important to you? If not, why are they important to Rachel?

RSB: Yeah, so that is important to me. It's a band that my older brother Jib introduced me to – Jib in fact being the only member of my family who's been to Antarctica. But entirely unrelated to that, he's a big fan of Pink Floyd. He's eight years older than me, and introduced me to their stuff when I was in my mid-teens, I suppose. And the album he had—on CD, in those pre-Spotify days—was The Wall. I listened to it over and over, as is my habit with the very small amount of music that I get really into—and so for a long time it's been a big favourite of mine.

The reason I use it in the book is firstly because it's a connection between Rachel and the “heroic” Adam who has introduced her to this to this music, and secondly, walls being a very thematic part of the novel, y’know, she’s cut off from the rest of society, we discover early on there are some emotional divisions between her and Adam, there’s literally a mountainous wall between her and the rest of her team, and also some of the song titles on the album reflect what’s happening to her throughout the book. ‘Mother’, ‘Empty Spaces’; there are various others. Some of it was a bit of an accident while I was writing, and I couldn't really believe my luck that it seemed to work so well. So I was very keen to try and weave all that together.

ASHS: Now, in there, on the way to Antarctica, there was a very quiet Falklands reference. I think just the one. Were you tempted to make more of your home country’s role in Antarctic exploration?

RSB: Well, the Falklands, as you know, has a very strong history with the Antarctic and Operation Tabarin and all those things, and to this day the BAS ships are registered here in Stanley. RRS Bransfield turned up when my family was living here in the early 90s, and Jib was working at the hospital, I think as a driver. They needed a steward who could join tomorrow, before they sailed South, and he said “I’ll do it!”—so off he went and did a couple of seasons. But other than that, I couldn't really justify getting any more Falklands mentions into the book!

ASHS: While we're on the Falklands, I'm aware that you started work on Whiteout some time ago. We'll circle back to that in a bit; but is the Falklands a good place to write a novel? Would-be writers have all sorts of ideas about finding the perfect working environment: a yurt, or an Anatolian cave, or David Cameron’s gypsy caravan or whatever it was. And then Trollope just boshed out 300 words on the train each morning, which is annoying as hell. The Falklands seems like a peaceful, out-of-the-way kind of place—albeit with dreadful connectivity—but is that good?

RSB: Bizarrely, if you've got a picture of the Falklands in your mind's eye as a solitary environment where you could come and get some peace and quiet and just get on with writing, that is true of certain places in the Falklands… but not Stanley. And in fact, I wrote most of this book when I was living in London.

ASHS: A famously quiet place!

RSB: You say that, but what I used to do is I would take a week off work and I would just lock myself in my flat and nobody would know I was there. Nobody pops in to see you in London. Because it's two train rides and then a bus, and whatever else. Whereas here, if I was to take a week off work and just say, “I'm gonna write,” you know every other day someone's dropping by, or people just see you around, you end up getting invited to things. It's a very, very socially busy place, Stanley. I did write some chunks of it on the RAF Airbridge, flying between the Falklands and UK...

ASHS: I mean, there’s nothing else to do…

RSB: Quite. And my addendum to all this is I'm now writing my second book and I have written most of that here in the Falklands. But the secret to that is most of it has not been done in Stanley, where I live. I’ve rented a shepherd’s hut, out in the sticks, and driven out there—and I'm sure the farm-owners think I'm bonkers because I turn up and just lock myself in the house for a week or ten days. “Surely he could have done this in Stanley?!”

“Nobody pops in to see you in London. It’s a good place to write.”

ASHS: Except, if memory serves, you have an anecdote about your neighbours in Stanley, and whether or not you’re doing any work?

RSB: Yeah. This being my first book, I obviously have to make a living other ways. So I do writing and journalism, mainly for Formula 1, the official website and their social channels and things. And I do things like script writing for videos that they put out, and features writing and commissioning and editing and all sorts of different stuff for them—but I do this from home. I moved into an old house here in Stanley two years ago, and one of my neighbours has lived across the road for a long, long time, and I went over to speak to him after I'd lived there a couple of months, and he very abruptly said, “I don't get you at all. You never seem to go to work.” So I said, “Oh no, I work from home”—and his face crinkled up like I’d just told him I’d been abducted by aliens.

Eventually he said, “What do you mean? Like, on the computer?” I said “Yeah,” and he went “Right. OK.” Now, because I’m working for Formula 1, sometimes I do very odd hours. For example, the Australian Grand Prix: night shifts from 10pm til 8am, for three or four days. And after one of these my neighbour knocked on the door for some reason, to find me still asleep at what by everyone else’s standards was the middle of the working day. A week or so later, a mutual friend of ours came around to see the new place—it was about 11 o'clock in the morning—and he didn’t know which one it was. So he asks my neighbour, “Which one’s Robbie’s house?” and he says, “That one up there. But don't bother, he'll still be in bed.” So yeah: he just thinks I’m an absolute layabout.

ASHS: So, you’re a trained, experience journo…

RSB: Yeah, I did an English degree, and then I came back here for a couple of years and did various things working with tourism, and throughout all that time I did occasional bits of work at the Falkland Islands’ Penguin News—the first place that ever paid me to write anything. I decided I needed to do something ‘proper’, so under a combination of duress and encouragement from various people I went away and did a postgrad journalism course, the NCTJ, which taught you shorthand and law and how not to libel people. And then I got a job on a paper called the Buckinghamshire Examiner.

ASHS: … but this is your first novel? Or your debut published novel?

RSB: Good question. I've got probably two or three novels in folders, at various stages of drafting, and one that I had finished but that just wasn't very good and I was about to start rewriting it when I hit upon the idea for Whiteout and dropped everything else I was doing.

This was in 2017. I was working for the Daily Mirror, and was on my lunch break, and I found this article on the BBC website, which contained the declassified script that would have been broadcast in the case of a Cold War nuclear emergency. Y’know: “keep calm and conserve your water supplies”—all that kind of stuff. And I thought it was just an amazing piece of writing.

ASHS: Imagine having to record that, in peacetime, but thinking one day it’d go out while there’s black rain falling, or whatever.

RSB: Yeah, exactly. And the article was talking about how they wanted the person who would read it out to be a familiar voice—a newsreader or something—because in those circumstances everyone would be craving familiarity and it would give a sense that civilisation was carrying on at some level…

ASHS: Stephen Fry.

RSB: It would be these days, wouldn’t it? But in the book Rachel thinks, you know, who is this guy sitting in a recording studio, in his comfy slippers? He’s not actually living through this! And she sort of hates him at that point. So I read that, and then I remembered I'd thought for years and years Antarctica would be a great place to set a thriller, and bing!—it was just one of those moments which are all too rare but so exhilarating, when you just can’t get the notes down fast enough. Within 24 hours I’d written my rough outline, and essentially from then to now the key elements have remained the same.

“I found this article on the BBC website, which contained the declassified script that would have been broadcast in the case of a Cold War nuclear emergency.”

ASHS: And how long did it take from there to finished 275-page product…?

RSB: OK, so, as you know, you can’t simply send a manuscript to publishers. They just don't bother even opening the mail. You pretty much have to have an agent if you want to get published in the traditional way. You can obviously self-publish; but it’s a lot more work, and you have to do all the editing yourself, and market it, and I didn’t know how to do any of those things, so essentially I just couldn’t be arsed. So I thought I'll send it around to agents in the hope of getting signed—but very much more in hope than expectation. Y’know, the number of submissions versus the number of people they sign up is vanishingly small.

I’d already had a version of the book assessed by this very brutal editor/novelist/consultant lady who said, ‘You’ve got something here, but there are a few things you need to work on…’ So I’d done all that and sent off my first three chapters and synopsis to about a dozen agents, got one request for the full manuscript, and… she politely declined.

So I did another dozen—and obviously you’re trying to pick agents who typically represent the sort of book you’ve written, not Faber poets or whatever—and again I didn't get anywhere. So at that point you’re thinking think okay, this isn’t them failing to recognise my literary genius; the book just isn’t good enough.

So I sat on it for another year, made some fairly minor changes, and then sent it out to another dozen agents, one of whom asked me for the full manuscript. Then I get the magic email asking if I’m free for a call. I'm very, very excited by this point. So we have the phone call, and it’s all very professional and everything else—but we didn't really click. Oh, and she said the book needed about another 20,000 words.

ASHS: How long was it, originally?

RSB: About 75,000. My heart just dropped. Like, ‘Where the hell am I getting 20,000 more words??’ This is a book set in Antarctica. Not too many landmarks; a very small number of characters… So I was pretty stumped by that. And also I liked the fact that it was a taut piece of work.

Anyway, meanwhile, I’d gone back to the last eleven agents and said, ‘I'm now getting some interest,’ and at this point two more of them got back to me. I had phone calls with them both, and just got on with them much, much better. They both had notes; but neither of them wanted me to write another 20,000 words!

Still, weirdly, that first agent I never signed with is one of the most important people in my publishing story, because without her interest I might never have caught the attention of the brilliant agent I’m so glad I did sign with, Jemima Forrester, who’s done such a fantastic job for me.

So, now I’ve got an agent, and to be honest, I was fairly confident I would get a publisher at that point.

“Where the hell am I getting 20,000 more words?? This is a book set in Antarctica.”

ASHS: What year is this?

RSB: Christmas 2020. So we did two rounds of edits together—for which she gets paid nothing, by the way, if the book never goes anywhere—two rounds fairly quickly, I’d say within six months, and then she says to me, “It's ready. I think it's brilliant. I'm going to send it out this Friday. Be prepared and be braced because this can move very, very fast and I will need you to be available to discuss things.”

Annnnnnnnd… nothing.

We’ve all read stories about debut authors signed with a six-figure deal after a high-profile auction. Well, we get nothing. Nothing. And this goes on for quite a long time and then Jemima starts doing a bit of chasing and we start getting the rejections and they just keep coming and they're all very nice, and she’s saying “We only need one, and then”… But we just never got it. We did a whole year of that.

ASHS: Christ. I mean, it’s fatiguing just listening to it.

RSB: Yeah. And then she said, “Okay. Write another one.”

ASHS: Fuck.

RSB: I mean she didn't say it that bluntly. But it was very depressing. Because, y’know, frankly I thought this was the best thing I'd ever written, by miles. And also was the best idea I've ever had, by miles. If I couldn't sell that…?

So, anyway, I did start doing that. And the novel that I started then is now going to be Book Two. But then, out of nowhere, a year, two years later, whatever it was, Jemima messages me and says, ‘One of the editors from Hachette has just moved to HarperCollins. He needs to start building his list. He's looking for survivalist fiction, and I immediately thought of you. I've sent it over to him.’

ASHS: Another level of total fluke.

RSB: A whole third level. And we're still not at the point to celebrate. Jemima’s very, very good at calming me down. A brand new editor can’t just sign a book like that. He has to go to eight other departments, y’know. But she's keeping me informed, we're talking every couple of weeks. Then it comes down to the acquisitions meeting. There are board members at this meeting. People who can sign a cheque.

The meeting is always on a Tuesday. So obviously, that Tuesday I'm hopping around like a kid who needs a wee. Business hours come and go. That doesn't necessarily mean anything: Jemima e-mails me at midnight, sometimes. Wednesday comes and goes. Thursday. And on Friday I finally crack and phone her, having convinced myself that it’s a no, and she says “Oh my God, I'm so sorry: I meant to tell you. Someone was on holiday, so the meeting was postponed by a week.”

So the next week the meeting isn’t on the Tuesday, it’s on Thursday. I’m chewing the furniture at this point. And after it I get an e-mail from Jemima, forwarded from Morgan Springett, the editor, saying ‘Sit tight. I’ve had to field this to another department. But hopefully we’ll have some news for you tomorrow…’

ASHS: The tension in this story’s worse than in your bloody book…!

RSB: I know!! Anyway, finally, the following day, Jemima calls me up and says we've had the offer. The whole process was absolutely tortuous. ‘Torturous?’ ‘Tortuous?’

ASHS: Both!

RSB: Well, yeah. Had the Harper deal not come off, I would have been crushed, after all that build-up. But what illustrates to me how close it was to not coming off was that after she sold it for the UK market, Jemima then went out to sell the US rights as well. So we had to go through it all again…

ASHS: I’m not sure I can.

RSB: … And we very nearly secured another Big Five deal—I can’t remember which publisher, but they were very keen, the editor loved it, loved it, loved it—and then they didn't sign it because they had something vaguely similar already on the roster. Thankfully, we signed with a smaller publishing house, Crooked Lane Books, who’ve been excellent. But, that could have so easily happened with HarperCollins, and then one thing wouldn’t have followed another and then I've got nothing. So, y’know, you’ve gotta do the work… but there is so much luck involved.

ASHS: Back to Antarctica. You’ve fessed up already that you haven’t been there yourself. Not that everything in a debut novel has to be autobiographical; but that is typically fertile ground. How much personal experience did you want or need to mine for this? Or did you just spend a long time rummaging in museums and/or libraries?

RSB: You’re right—I've never been to Antarctica. But I read a lot of books and blogs and things, and follow lots of people on Twitter and Facebook who work there and have been there and have lived there… And having said all that, I've absolutely written things which I'm sure will enrage people.

“One of them has been awarded the Polar Medal! I hope he buys it, but never reads it.”

ASHS: There's a get-out clause in the Acknowledgements, isn’t there?

RSB: Yeah, well, I stole that from people like John Grisham and Michael Crichton, who do that all the time. I kind of work by the rule that obviously you try and get everything as right as you can, but you’re never going to get everything right if it’s a subject that you don’t know intimately. So some mistakes will be things I've got wrong because I've never been there; other ones I probably needed to make for plot reasons or whatever. And the Antarctic is a remote enough place… It's a bit like when a doctor is portrayed on TV: most people watching aren't doctors.

ASHS: And most doctors probably aren’t watching.

RSB: Right. Living here in the Falklands though, I have had lots of friends and acquaintances excitedly ask me about the book and when it’s coming out, and saying they’re gonna buy a copy—and lots of these people, I’m terrified of them reading it because they know all about the Antarctic. I mean, one of them has been awarded the Polar Medal! I just… I hope he buys it, but never reads it.

ASHS: Speaking of books, I was particularly caught by the very specific list of books that were left in One Ton Hut.

RSB: Now, One Ton Depot was a real thing, and was the place where Captain Scott's team had left provisions, for the group which trekked back from the South Pole. They didn't quite make it, of course—they were 11 miles short. But it wasn't a hut. As I understand it, it was basically a hole in the ground. In Whiteout, it is a hut. And as you’ve guessed, it’s based exactly on the Recluse hut, which is in Stanley Museum. I was here for a visit one Christmas, when I was living in London, and I went down there for a nosey around—size estimates and so forth—because I knew it was basically going to serve my purposes.

As for the book collection, I’m pretty sure that’s based either on books that were in the Recluse hut, or Discovery Hut—Scott's hut, where McMurdo Station is now. There's Moby-Dick, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, The Story of Bessie Costrell by Mrs Humphry Ward, and the Bible. And that list was definitely based on something because until then I had never heard of Bessie Costrell. It sounds so much of its age, though, that I kept it in there just for that realism.

ASHS: You live in a town where it's entirely possible to bump into polar experts in the shops. We know there are overt Pink Floyd references drifting about in the text. Are there also sneaky ghost quotes from polar history?

RSB: There are. And they are mostly found in Rachel’s diary entries. I was probably laying it on a bit thick when I wrote the first draft, and everything she wrote was either from the nuclear broadcast or was a Pink Floyd line or was from Scott’s expedition logs—so when I first signed with my agent she thought that maybe I should tone things down a bit. But if you’ve avidly read Scott’s diaries you might still spot the odd allusion.

ASHS: Was there a lot of teeth-gnashing from you about that?

RSB: Well, there was a bit of horse-trading. But actually you do have to be careful with those kind of ‘sampled’ materials, because you might have to pay for them.

Jumping back into the publication process for a moment, Morgan sent me an email one day which I could tell had been written in a cold sweat in the middle of the night. This is just before we actually go to print. He said ‘Have you got Pink Floyd lyrics in the text here…?’ Luckily, one of the things I'd read before I started writing this was don't use lyrics and things. Relevant song titles you can probably get away with, but not lyrics, or not explicitly. So I'd been pretty careful, and when we went back through it there were a couple of things, which he thought were alright anyway because they’re in general circulation.

But then I had the cold sweats and woke up in the middle of the night and wrote back to him, saying, ‘Hang on a minute. Do we need to get clearance to use the radio broadcast??’ Because I’d used the actual script. And he said, ‘Oh, I don't think so. Let me check with legal.’ And legal said ,‘You absolutely do need to get clearance for that!’—but the thing was I didn't know who owned it, whether it was BBC copyright or HMG or who. So I had to write to them and say, is this yours? And if so, can I use it? How much will it cost? Months went by and the publishers were getting very nervous.

And eventually a very nice lady wrote back to me and said, ‘This is BBC copyright, but I'm happy for you to use it. And because it's only 400 words there’ll be no charge.’

So I was very, very relieved. Even more nicely, she then said, ‘I've read the entire book and I think it's really good.’

ASHS: She give you anything you could stick on the cover?

RSB: She didn't—but I’ve had some really nice comments from other writers, sometimes even by people whose stuff I’ve read, which is pretty exciting.

“As a writer you’re not going to get very far if the only books you write are about somebody who's exactly like you.”

ASHS: You said you were working off books, blogs, conversations with people who’ve been there and done that. But then at the other end of the world there are references to hipster bars in Shoreditch, distressed furniture in North London homes, IT consultants, etc. Is there some tweaking of the nose of armchair travellers? People like me with the portrait of Scott on the wall but no actual skin in the game?

RSB: Yeah, a little bit, I think. And also the contrast was just too perfect, really. In the middle of a desperate attempt at survival in unimaginable conditions Rachel looks at the antique wooden chair and floorboards and reflects that they’d “go” perfectly… And the kind of North London Twitterati, I mean it's just too easy to take the piss, isn't it?

ASHS: And perhaps also the middle-class environmentalists, who may share Instagram stories about ice shelves calving, but are hardly about to leave their families behind to ensure Antarctica’s protected, and wouldn’t last five minutes down there if they did.

RSB: Exactly. To Rachel’s credit, I also wanted to draw out that contrast in her situation. She’s in the shit from the get-go of the book, and yet she's left a very, very comfortable lifestyle to do this. And when she was living that comfortable lifestyle she was really not enjoying it. So those kind of things just elevate her situation, I hope.

ASHS: Now, on the subject of Rachel, what decisions, assuming there were conscious ones, had led to your having a female protagonist?

RSB: Yeah, it's a really good question. Everything I'd written before had a male protagonist; but Whiteout, when it came to me, immediately the main character was a woman. So it wasn't a conscious decision, in that sense. Having said that, I don't think the world necessarily needs another male-led thriller. I wanted to do something a little bit different if I could and I thought that would be a point of difference.

I’m aware of the pitfalls of a man writing “as” a woman, so I was pleased that many of the earliest readers of the manuscript were women, and likewise when I was lucky enough to get interest from agents I was very keen to sign with a woman precisely because of that reason. Jemima pointed out a few things about Rachel's role as a mother, for instance: she didn't have any children, and neither do I, but she said, “I know your sister does and I think there are things in this that don't ring true. You might want to ask somebody who's been through this.” So I did do that, and my sister gave me some really good information which I then went back and incorporated.

Same as with the Antarctic stuff, you’ve got a duty to do your homework. But as a writer you’re not going to get very far if the only books you write are about somebody who's exactly like you.

ASHS: The blokes, then. There’s a small handful, with names that range from A to Z. Presume that’s not by chance?

RSB: No. Did you ever read Z for Zachariah?

ASHS: Sure. In Yr8, or thereabouts?

RSB: As schoolchildren in the Falklands, we all read Z for Zachariah, right? The basis of the novel, as you may remember, is there’s been a nuclear disaster. Ann, I think her name is, is the protagonist—again, a female protagonist, written by a man—and her family escapes the effects of radiation because of the valley they live in. Then the rest of the family go off looking for survivors but she stays put, and then one day a man turns up, and she calls him ‘Zacharia’. It's very different from my book, but there are obviously parallels. I wanted a nod to it, mainly in honour of the teacher, Veronica, who introduced me to it.

ASHS: We’ll come back to the nuclear theme in a minute. But the crux of Whiteout is Rachel’s desire to save the planet from oil exploitation. Are you yourself, to any meaningful extent, an environmentalist—and if so, what's your view on the Falklands and the oil game?

RSB: Ideologically: yes, I'm an environmentalist. In practical terms of what do I do? I’ve literally just installed the kerosene boiler in my house. I mean, I fundamentally believe in climate change, I’ve done some tussac planting, I've been penguin counting for Falklands Conservation… I've done at least four days of that! Really, I think I'm as bad as everybody else.

Oil in the Falklands? It's a tricky subject. I suppose fundamentally, I don't really think we should be digging out any more oil from the Earth. But having said that, you know, in the real world, we can't turn everything off overnight, never mind the number of things made out of plastic we would have to do without.

The Falklands is a strange place in that it has historically always been vastly too over-reliant on one industry or another. When the Gold Rush was happening, it was all about servicing ships going around Cape Horn. Then when that fell apart it was sheep-farming for a hundred years until that fell apart. And then for the last 30-odd years it's been deep-sea fishing, which I have a lot to thank for. The Falkland Islands’ government paid for my university, so I wouldn't be degree educated without that. But the Falklands is so small that if the fishery disappeared tomorrow, we would be in very, very serious trouble as a country. So, we do need to diversify.

I think in an ideal world, it wouldn't happen. But it’s not an ideal world.

Of course, the threat of oil exploration is only really the primary driver for the plot of the novel—the instigating incident for getting Rachel out to Antarctica. Having said that, some of the early reviewers have pointed out how some of the circumstances that lead up to it now seem a bit scarier given what's happening in politics in other parts of the world.

“There are now any number of flashpoints that it's not inconceivable could lead to the situation Rachel finds herself in, so by no design on my part, the novel now feels a little more prescient than it actually was.”

ASHS: Well, it’s funny you should mention that, Rob… Plenty of authors have been cursed with bad luck in terms of the timing of their publication. Y’know—you write a thousand-page zinger about Kamala Harris’s first term in the Oval, and then circumstances shift. But is it possible that a book you started eight years ago with a nuclear catastrophe as its underpinning is now more of a hot topic, as a by-product of its long gestation?

RSB: Well, curiously, one of the big themes of this book is isolation, of course. And when Jemima was first pitching it around to publishing houses it was right in the middle of coronavirus, and the UK was in lockdown. And a lot of those nicely-worded rejections that we got said, ‘We’re not sure that our readers, having been locked up, away from everybody they love for two years, really want to read a book about being locked up and isolated from everybody you love.’

That was possibly a bit of an easy excuse; but when we did eventually find a publisher lockdowns had become a thing of the past, certainly in the UK. So if anything I think initially the circumstances possibly hurt the book. Lots of people who read it, you know, other published writers, other published novelists, said, ‘Yeah, this is just bad luck, bad timing, it'll come good in the end’—and of course as a desperate first-time novelist you don’t really want to hear that, and also you’re not sure that you believe it. So, y’know, I was pretty ticked off with that at the time.

ASHS: But the same script that was perceived then as too Covid-y might now be perceived as being bang on the money in terms of revived nuclear concerns.

RSB: Well, that's an interesting point. So when I wrote this, one of the reasons I had this as a theme in the book is because it felt to me like fiction—in both novels and films—had really moved on from nuclear war as a threat. When I was growing up, James Bond films were about the bad guys trying to steal a nuclear warhead. I'm interested in history, I’ve read a lot about the Cuban missile crisis, things like that, and I found that all fascinating. But when we got into the 2000s and onwards, it seemed like that as a threat had been forgotten, and it was much more about things like AI, robotics, diseases: technology getting the better of humanity. And I just thought this would be a bit of almost nostalgia for a bygone age! I kind of wanted to be like we've all been focused on these other threats—biological, technological—and there's this other one that's been there the whole time, still is there, and we’ve just somehow decided ‘Oh, that's never gonna happen.’

As you say, though, I think at the time I wrote the first draft we were probably at a fairly low threat level, since nuclear war first became a possibility.

ASHS: Five minutes to midnight, on the Doomsday Clock, rather than one minute?

RSB: Yeah. But now I think you're right. Geopolitically, things are much more unstable. Early in the book, Rachel speculates as to what might have happened, thousands of miles away from her—and there are some very vague hints about what that cause might have been. But I was having to reach for those at the time—whereas now I could add about another five! I even considered briefly whether I should slot in a Ukraine mention; but in the end I decided no, that's just gonna date it. But as you say, there are now any number of flashpoints that it's not inconceivable could lead to the situation Rachel finds herself in, so by no design on my part, the novel now feels a little more prescient than it actually was.

ASHS: You mentioned a Book Two. Am I right in thinking Whiteout is in fact part of a two-book deal?

RSB: Yep, that’s right. Both for HarperCollins.

ASHS: If I’m allowed to ask, then… What's next? Is it The Pit Lane Murders? (And if not, why not?)

RSB: Yeah, well, as a Formula 1 journalist, you will be shocked to hear that the first novel I tried to write was a Formula 1 Thriller…

ASHS: Get away.

RSB: Right? But no, my second book will not be about Formula 1, but it is another thriller, and it’s set on Deception Island, which is a more-or-less active volcano, just off the Antarctic Peninsula—in the Bransfield Strait, in fact. So I’m knee-deep in that at the moment, and currently just waiting for notes from Morgan on all the many, many things I’ll no doubt need to change. And then I have another which I’ve written half of, because I got bored of writing this one halfway through...

ASHS: I’m starting to spot a theme here…

RSB: Yeah, yeah. But that one will remain on the backburner for some time.

ASHS: Now Backburner’s a great name for a thriller.

RSB: Ha. About a novelist who keeps getting distracted…

Whiteout is available now, from HarperCollins (UK) and Crooked Lane Press (USA)